Tim Davis

Nature Notes series and more from Berrynarbor's resident ornithophile.

NATURE NOTES -

SWAN-SONG

with Tim Davis

Swans don't sing, I hear you cry! But they do - after a fashion - though not quite with the operatic, pre-death aria ascribed to them by the Ancient Greeks.

With autumn in full swing and winter just around the corner, now is the time of year when Britain's full complement of wild swans will be present on our wetlands and surrounding fields, in particular those of conservation organisations such as the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT), RSPB and the Wildlife Trusts. The UK is host to three species: the very familiar mute swan which is a native resident with its famous Royal connection, the whooper swan and, the smallest of the three, Bewick's swan, which like the whooper is a winter visitor from far northern climes.

Mute swans are actually far from mute. Cygnets make loud whistling calls, but once they reach adulthood their main noises become grunts and snorts, especially during the breeding season. One of the best places locally to watch - and hear - mute swans is Wrafton Pond, easily reached along the Tarka Trail from its starting point at Velator in Braunton. One or two pairs nest here each year and the male's vocalisations, when defending its territory or seeing off a rival suitor, can be quite alarming!

Both whooper and Bewick's swans are vocal throughout the year, especially when on water and in flight. The calls of these two winter visitors are however quite different.

Bewick's swans make a soft, almost musical bugling call. They breed on tundra in Arctic Russia from where they make a 3,500-kilometre journey to the warmer winter climes of the UK, mainly in eastern England, Lancashire and around the WWT Slimbridge reserve on the Severn Estuary. Whilst numbers visiting Slimbridge have fallen in recent years, last winter's total of 128 birds included 33 juveniles, which made it the most successful breeding season since 1966. A winter visit to Slimbridge provides the opportunity to see the swans up close, especially during the late afternoon feeds on the Rushy Pen - which you can enjoy whilst seated in a heated observatory, hot chocolate in hand.

Whooper swans are highly vocal, their loud trumpeting calls like a 1920s car horn! They breed in Iceland and fly non-stop at very high altitudes to wintering grounds in Scotland, Northern Ireland, northern England and East Anglia. A few 'overshoot' their intended destination - especially if there is a strong tail wind - and turn up in Devon from time to time, like the six birds [pictured] which spent a short time on Lundy. Others have appeared on Braunton Marshes.

What further differences are there between the three species? Adult mute swans have red and black bills, while whooper and Bewick's have yellow and black bills, a key difference being the greater extent of yellow on the whooper's bill - which you might be able to pick out in the photo montage. Mutes and whoopers are roughly the same size in length and wingspan, while Bewick's are smaller (about four-fifths the size of the other two), with a distinctly shorter and straighter neck than a whooper's.

Altogether there are seven species of swan worldwide, the other four being trumpeter (the largest of all and found in North America), tundra (arctic North America), black-necked (Falkland Islands and southern South America) and black (Australia). All occur in wildfowl collections in the UK. Of these, black swans, which have long been a feature (and the emblem) of Dawlish in South Devon, were first imported into the UK in the late 18th century and first bred in the wild in 1851 in Surrey. They now occur widely as introductions or escapes. Black swans are also known to form hybrid pairs with mute swans and produce offspring - known as 'blute swans'!

Clockwise from top left:

Bewick's swans (photo: Jeff

Hazell), mute swan (photo: Alick Simmons) and whooper swans on Lundy (photo:

Nigel Dalby)

My Swansong

As a teenager growing up in Barnstaple in the late 1960's I was totally unaware of the riches of the wildlife around me until I met someone who introduced me to Lundy, and subsequently to the joys of 'birdwatching with a purpose' (e.g. carrying out monthly counts of wildfowl and wading birds on the Taw/Torridge Estuary) and to discovering the many wild places that took me to. Little did I know that this would open the door to a 40-year career working for the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), The Wildfowl Trust and WWF International before returning to North Devon in 2001 to establish, with Tim Jones, our nature-focused consultancy.

Over the past 21 years living in the Sterridge Valley, once again involved in estuary counts, recording birds and other wildlife at home, on Lundy and around North Devon, and more recently doing bird surveys for the National Trust on some of their coastal land holdings, the enormity of habitat loss and wildlife declines through human activity has hit us with the force of a brick - whether here in North Devon, elsewhere in the UK, or further afield. A recent assessment by Tim J of more than 50 years of counts on the Taw/Torridge Estuary revealed a 68% decline in average peak numbers of wintering waterbirds. And where 20 years ago the skies above the valley in spring and summer would be filled with locally breeding Swallows and House Martins and a dozen or more Swifts, nowadays the Swallows and martins are many fewer in number and Swifts have all but gone.

Collectively in the valley and village, we live within the North Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) but sometimes we risk confusing what we think of as 'beautiful', with what is good for nature. In these times of a rapidly changing climate and declining insect and bird populations, we can all do our bit. That might mean thinking about how to make a bit more space for wildlife in our gardens, farm fields, hedges and verges - letting rough corners stay rough, allowing a bit of gorse or furze here and there, or restoring ponds or wet flushes that can help resist drought. A lot has changed with agricultural policy and farming practices. Encounters with Yellowhammers for instance, once common across North Devon, are now rare as the seed-producing crops on which they used to depend in winter have largely disappeared.

There are of course plenty of good things happening. One example is the recent clear-felling of swathes of mature Sitka spruce and western hemlock from Woolscott Cleave. In spite of the dramatic change in appearance, this will allow natural regeneration of native broad-leaved trees such as silver birch, hazel, rowan and willow, along with sweet chestnut which may take the place of the stricken ash, supplemented by some additional planting of oak.

As awareness of our fast-diminishing wildlife grows, a question I am increasingly asked is, 'What can I do to help?' If you have a garden, no matter how small, create a pond and/or a wildflower meadow, even if it's only a small patch. You will be amazed at how quickly your pond will attract wildlife, from pondskaters and whirligig beetles to dragonflies and damselflies, toads, frogs and newts. If you don't have a garden, a window box planted with nectar-rich flowering plants will attract pollinating insects, especially bees. If neither of these opportunities work for you, you can support nature-recovery projects by donating or subscribing to organisations such as Devon Wildlife Trust, the Woodland Trust, Plantlife, Buglife and the RSPB.

Good luck.

Tim Davis

32

NATURE

NOTES NO. 11

Silver-washed Fritillary

Tim Davis and Tim Jones

One of the great joys of the North Devon countryside in high summer, particularly in well-wooded areas like the valleys around Berrynarbor, is the sight of Britain's largest butterfly, the Silver-washed Fritillary.

These truly spectacular insects are on the wing from mid-June to early September (peaking in our region from mid-July to early August). With the larger females having a wingspan not much shy of a smaller human hand, the sight of one floating gracefully through the garden on a warm sunny day is likely to draw a little gasp of appreciation.

Every year we look out for the distinctive courtship flight of a male continually 'looping-the-loop' around a female as she flies in a straight line through the garden enticing him with her alluring pheromones. After mating, the female will lay her eggs, singly, in semi-shaded woodland around the base of trees, in crevices of bark or in moss, usually one to two metres above the ground. The larvae hatch within a few weeks and go into hibernation. In spite of their impressive dimensions as adult butterflies, they overwinter as tiny black caterpillars hidden away in the leaf litter, emerging on warm days in spring to bask on dead bracken and other such surfaces that warm up more quickly than the surrounding vegetation.

The caterpillars feed on the leaves of common dog-violets and, if the weather remains favourable, grow rapidly before pupating in early summer and emerging in their adult attire of orange-brown upper wings, delicately marked with black cross lines and bold spots, contrasting with the stunningly silvered-green underwings.

A freshly emerged Silver-washed Fritillary

A mating pair, showing the silvery-green underwing

The adults like to drink nectar from buddleia, sedums, single daisy-like flowers including asters, as well as wild bramble and hemp-agrimony, so finding room for any of these in your garden will increase your chances of seeing them.

The decline of traditional deciduous woodland management, such as coppicing and pollarding, has been problematic for silver-washed and other British fritillary species because the periodic flushes of violets that used to thrive in the regular rotation of sunny clearings and rides no longer occur as they once did.

The similarly-sized high brown fritillary clings on in the Heddon Valley thanks to conservation management by the National Trust, and the delightful but much smaller pearl-bordered fritillary is now only found in a handful of Devon localities, having once been common and widespread.

Photos by: Tim Jones

29

NATURE

NOTES NO. 10

Woodpeckers

Tim

Davis

Those of you who enjoy watching birds in your garden will very likely be familiar with the most common of the three species of woodpecker that occur in Britain: the great spotted woodpecker. Over the last two decades this characterful member of the British avifauna has increased its range considerably, an expansion documented from the 1970s onwards. Bird Atlas 2007-11 (the published results of the third national survey of its kind since the first covering the years 1968-72) revealed that 'great spots' now breed as far north as the north coast of Scotland, though in much lower densities than further south.

Factors that have potentially contributed to the species' success include: a national decline in starling numbers and consequent reduced competition for nest sites; increases in availability of dead and dying wood, which are important for both feeding and nesting; and the growth in supplementary food provided by the five million or more householders across Britain who hang peanut, seed and suet feeders in their gardens. Over the past autumn and winter months in our Sterridge Valley garden, at least three great spots (two females and a male) were coming to feed on the suet squares at our bird feeders.

Great spots are instantly recognisable. About the size of a blackbird, they have basically black and white plumage, the most striking feature being the large, white oval 'shoulder' patches at the base of each wing. In flight the black wings show four 'dashed' white bars. Separating males from females is easy: the small red square on the back of the male's head is lacking in females. Juvenile birds resemble paler adults but have a distinct all-red crown, which gradually disappears in autumn as the young birds mature into full adult plumage.

The two other woodpecker species native to Britain are the much larger green woodpecker (roughly jackdaw size) and the increasingly scarce lesser spotted woodpecker, the smallest of all woodpeckers, about the size of a house sparrow.

In recent years the number of green woodpeckers in South West England has been declining, in contrast to central and eastern England where numbers have increased. The reasons for this are not understood but may be linked to reduced availability of ants which are the species' principal food. Green woodpeckers can still be encountered in the Sterridge Valley, usually first noticed by its loud, laughing call - from which its colloquial name, 'yaffle', is derived.

Sadly, numbers of 'lesser spots' have been in decline since the early 1980s. There were just four confirmed breeding records in Devon during the 2007-11 Atlas survey, only one of these in North Devon and there have been few if any more recent sightings. They occur almost exclusively in mature broadleaf woodlands and old orchards, and the loss of the latter, along with other factors such as limited food availability (they feed mainly on insects), may have played a role in the species' decline.

Left-right: great spotted woodpecker (Ron Champion), green woodpecker (Dave Scott) and lesser spotted woodpecker (Brian Gibbs)

For a wealth of information about woodpeckers, visit www.bto.org and enter 'woodpecker' in the search box.

40

NATURE

NOTES NO. 9

A tough

time for nesting birds in 2021

Tim

Davis

In December the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) released its first assessment of the 2021 breeding season. Two surveys carried out across the country every year, the Constant Effort Sites (CES) scheme and the Nest Record Scheme (NRS), both suggest it was a disastrous year for many of our smaller birds.

In the CES, which has been running since 1983, bird ringers monitor birds in exactly the same places, over the same time period, at regular intervals through the breeding season at over 140 sites throughout Britain and Ireland. This standardised approach allows population trends to be calculated, including the abundance of both adults and juveniles, for 24 species of common songbird. Of these, 18 produced significantly fewer young last year, the outcomes being consistently poor for migrant warblers and resident tits, thrushes and finches alike.

Meanwhile the NRS gathers information on the breeding success of birds by asking experienced volunteers to find and follow the progress of individual birds' nests (without inadvertently disturbing those nests). Each year, hundreds of volunteers submit observations of nests they have monitored. This information is combined to assess the impacts that changes in the environment, such as habitat loss and a warming climate, have on the number of fledglings that birds can rear. Some people watch a single nestbox in their back garden, while others find and monitor multiple nests of a whole range of species. As with all BTO surveys, the welfare of birds is paramount, and all nest recorders follow an established Code of Conduct designed to ensure that monitoring a nest does not influence its outcome.

In 2021 these two schemes showed that breeding success was well below average across the UK thanks to the poor weather in late spring and early summer. Birds either failed to fledge young, in part due to a lack of insects, or their fledglings succumbed to the cold, wet conditions after leaving the nest. In May, for example, rainfall across much of the South West was more than double the long-term average and it was also an especially chilly month, following a cold but exceptionally dry April.

Populations of most passerine species can bounce back quickly with a run of good breeding seasons, so let's hope that 2022 proves to be a bumper year for all of our songbirds.

For information about all BTO surveys, and how to take part, visit www.bto.org

Nuthatch - the combination of a very cold April and a wet May caused the failure of a breeding attempt in a Sterridge Valley nestbox last year (photo by Mark Darlaston)

Greenfinch, House Martin and Swift move into the Red

With UK population declines for Greenfinch (67% since 1969),

House Martin (57% since 1969) and Swift (58% since 1995), all have now sadly joined the Red List of 'Birds of Conservation Concern'. The fifth review of the status of birds in the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man, published in December, provides an assessment of the status of 245 species with breeding, passage (i.e. migrant) or wintering populations in the UK. The full Red List has grown by three to 70 species, now including Yellowhammer, Lapwing, Skylark, Puffin and Nightingale. The assessments are based largely on data gathered by volunteers through BTO-led surveys.

For more about the ups and downs of our bird populations, visit www.bto.org/our-science/publications/birds-conservation-concern

30

NATURE NOTES NO. 8

Return of the White-tailed Eagle

One of the most exciting happenings in my birdwatching life occurred in October 2020 on Lundy Island when a White-tailed Eagle flew almost over my head, no more than 30 feet up. It was one of those spine-tingling moments and an unforgettable experience. The two [large] Ravens in hot pursuit - one behind each wing - looked tiny by comparison!

Until that moment, the last known White-tailed Eagle on Lundy is documented as having been shot in about 1880, its stuffed and mounted remains now housed in Ilfracombe Museum. The species was formerly considered an occasional visitor to the island and is even believed to have nested on Lundy in the early part of the 19th century.

The British breeding population was hunted to extinction in the early 20th century, the last native individual shot in Shetland in 1918. A painstaking reintroduction programme, using birds of Scandinavian origin, began in Scotland in 1975, since when the population there has grown to some 150 pairs, centered on the west coast Highlands and Islands. On the continent, White-tailed Eagles nest around Scandinavian and Baltic coasts and in the wetlands of central and eastern Europe, some moving south-west in winter, occasionally reaching Britain. The European breeding range is expanding, and nesting is now regular in The Netherlands.

Recently, juvenile birds from the growing Scottish population have been released on the Isle of Wight. Now in its third year, the project has to date released 25 eagles, with most of these surviving and apparently doing well. Led by Forestry England and the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, the project aims to re-establish White-tailed Eagle as a breeding species in England after a 240-year absence. In all, some 60 young eagles are due for release over five years, with breeding activity anticipated from 2024 onwards once the earliest released birds reach maturity at five or six years of age.

Each eagle is fitted with a satellite tracker to enable their progress to be monitored. So far, the released birds have travelled widely, journeying across Britain as they develop the skills that, hopefully, will see them live long and productive lives. One bird released in 2020 crossed the English Channel earlier this year and has since spent time in France, The Netherlands, Germany and Denmark before heading back across the Strait of Dover in November. Another spent a long period roaming Exmoor, coming very close to Berrynarbor at one point, and it must be only a matter of time before one is spotted soaring over the village!

In spite of their extensive wanderings, the youngsters consistently return to the Isle of Wight and the Solent, suggesting that they see the island and adjoining mainland as their home - an encouraging indicator for eventual successful breeding.

As the eagles extend their breeding range, it's easy to imagine a pair one day returning to nest on Lundy, and perhaps also along the North Devon coast where long-ago sightings of White-tailed Eagles are recorded in the annals of Devon's birds.

Lundy's first White-tailed Eagle [inset] for more than a century flew over the island on 16th October 2020.

The tracking map [reproduced with permission of the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation] shows that it flew out north of the island before returning to rest for a time near the north lighthouse, before returning to the North Devon mainland where it roosted in cliffside woodland. [photo: Dean Jones]

You can read more - including the answers to frequently asked questions about White-tailed Eagles - on the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation website at www.roydennis.org.

Tim Davis

28

NATURE NOTES NO. 7

Tracking the

Cuckoo's Decline

Tim Davis

Over my years in the Sterridge Valley,

I have often been asked why cuckoos are now rarely heard and, much less likely,

seen. Time was when the first cuckoo of

spring would be reported in TheTimes newspaper. Once a common sight in the UK, their numbers

have dwindled to the extent that the cuckoo is now a Red-listed Bird of

Conservation Concern. Surveys over the

past 25 years have revealed that we have lost over half of our breeding

cuckoos.

In efforts to find out why they are

declining, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) began satellite-tagging

cuckoos in 2011.This enabled them to be tracked from their

breeding areas in the UK to wintering grounds in the Congolese rainforests of

Africa. A lot of vital knowledge has

since been gained, such as how the different routes taken to and

from the UK year on year by individual cuckoos are linked to declines, and some

of the pressures they face on migration.

It has also revealed that they are in the UK for a surprisingly short

time (most only arrive in late April but start leaving again as early as June).

Breeding season surveys have shown, too,

that Cuckoos are doing better in some areas of the country than in others, the

decline in England being greater than in Scotland and Wales. Why this should be is not clear, so a greater

understanding of all aspects of the cuckoo's annual cycle is needed in order to

get a better idea of the factors driving the decline.

Male

Cuckoo, Lundy, May 2021 [photo by Dean Jones]

Whilst much has been learned, much

remains to be discovered.Researchers are now looking closely at how

dependent cuckoos are on - and how much their migration is linked to - the

rains of the weather system known as the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)

as the birds move out of their wintering areas and begin their long journey

back to the UK via West Africa.

At present the study has focused on

male cuckoos as they are larger than females and better able to carry the

5-gram tags more easily. The tags are solar-powered,

transmitting for 10 hours and then going into 'sleep' mode for 48 hours to

allow the solar panel to recharge the battery.

Once smaller tags are available, females and juvenile birds will also be

ringed, yielding new insights into how their migrations differ from the males

tracked so far.

In addition, identifying areas of

importance for wintering cuckoos will allow study of pressures there which may

throw more light on the losses of British cuckoos.

You can read more

on the BTO's website (www.bto.org) by entering

'Cuckoo Tracking Project' in the search box on the home page.

13

NATURE NOTES NO. 6

Meadow Magic - with Tim Davis

What

I have learnt over the 20 years that we have lived at Harpers Mill is that a

wildflower meadow is a wondrous thing. It

takes time and patience to create a meadow from scratch but the results are

hugely satisfying and the enjoyment derived from it increases year on year. For example, a few years ago the first

southern marsh-orchid appeared, most likely from long-dormant seed waiting for

the right conditions. Their number has

steadily increased until this year there were 75, mostly in the meadow but others

appearing in other parts of the garden nearby. Twayblade was another orchid that popped up

one year, but in its second year it got nibbled early on, probably by slugs,

and hasn't been seen since. Common

spotted orchid is another that suddenly appeared in a smaller meadow area and

has flowered twice in recent years. Then,

in late June this year, we made an astonishing discovery.

Greater

butterfly-orchid and (top to bottom) trembling-wing fly, western

bee-fly and small semaphore fly

There,

standing tall (over a foot high) and 'hidden in plain sight' amongst the ox-eye

daisies and meadow grasses was a greater butterfly orchid (Platanthera

chlorantha) coming into flower. Mesmerised, we stood transfixed, hardly

able to believe what we were looking at. Records of the species in the two most recent

'Floras' describing the plant life of Devon (published in 1984 and 2016) show

how rare it is: just two North Devon

records in the earlier Flora and only three more since then. The entry in the 2016 Flora describes it as

'occasional' and Near Threatened on the British Red List, occurring in 'well

drained, usually, base-rich or calcareous soils in woodland, commons and

meadows, pastures and roadsides, but very rare in North Devon'.

If you haven't

yet discovered the joy of a meadow, big or small, and would like to devote a

patch of your garden towards creating one, visit Plantlife's website

(www.plantlife.org.uk) and go to the blog page entitled 'What

is a meadow, why do meadows matter and how can you make one?'. Not only will you be adding variety to your

garden, but also helping to stem the loss of insects, which pollinate many of our fruits,

flowers and vegetables, and also help break down and dispose of wastes, dead

animals and plant material.

Such

excitements for us over the years have extended from birds to plants and more

recently, especially during the periods of pandemic-induced lockdown, insect

life. Of three new discoveries during the last month

(including on the morning I wrote this article!) one, of a tiny fly, occurred

in our kitchen. It was a mere 5mm long

but with longer wings which it was constantly waving around - hence known

colloquially as a trembling-wing or flutter fly; its scientific name is Palloptera

muliebris.

The

second was a western bee-fly (Bombylius canescens) which we photographed

nectaring on rockrose. This turned out

to be another fairly scarce species for North Devon, with currently fewer than

40 records for our region on the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) Atlas. And the third new fly - a 3mm-long small

semaphore fly (Rivellia syngenesiae) - we found, would you believe,

feeding on the stem of the butterfly orchid! There are four Devon records on the NBN Atlas,

just one previous record shown for North Devon.

Whatever

will we discover next?!

Photos:

Tim Davis and Tim Jones

9

Life at the Bird Feeders and in the Nestboxes - with Tim Davis

Several

years ago we bought the section of Smythen Wood that cloaks the steep slope

above our house. We quickly set about

making and putting up more nestboxes to add to the

five already in the garden. This year

the number has grown to 32, four of them now in the small nature reserve we

co-own [with John and Fenella Boxall] that runs alongside the lower part of the

hill up to Smythen. We feed birds [sunflower

hearts and suet] year-round, such that during the autumn, winter and the

approach of spring the garden supports a large number and variety of birds. Blue

and Great Tits abound, with smaller numbers of Long-tailed Tits, Chaffinches

and Goldfinches, along with year-round territorial Marsh Tits, Nuthatches and

Great Spotted Woodpeckers and, usually arriving in late February or March,

several pairs of Siskins which in recent years have stayed to nest in the

surrounding woods. Siskins will also

sit tight on the feeders, spilling seed out as they feast, often regardless of

our close presence. A great joy is to watch and hear male Siskins

song-flighting bat-like around the garden.

One of the garden boxes

this year occupied by Great

Tits

Somewhat

mystifyingly, two absentees from our regular garden guests are Greenfinches and

House Sparrows. Both are present up at Smythen [Greenfinches

though now in greatly reduced numbers due to the outbreak of disease that has

decimated their population UK-wide] but sightings in our garden have been few

and very far apart over our 20 years at Harpers Mill.

Hangers-on

[though not literally!] picking up what falls onto the ground from the feeders,

are Blackbirds, Dunnocks, Woodpigeons [one pair had a well-grown chick in a yew

hedge in early February this year], Carrion Crows, Magpies and Jays. Pheasants too suddenly started appearing some

ten years ago and now nest, with varying degrees of success, in the nearby

field margins. Witnessing what just a

few can do to a garden and wildlife, especially larger insects and newly

emerging froglets and toadlets as they spread out around the garden, makes the

mind boggle at the impact of 45 million or more released annually in the UK for

recreational shooting.

A

regular visitor to the feeders this year has been a male Sparrowhawk. If its first pass at break-neck speed in

search of a meal has failed, it will sit on the crossbar of the feeding

station, sometimes for minutes on end, its wild glinting eyes constantly

scanning the nearby bushes for a potential victim. Meanwhile an immature Buzzard is more

interested in what it can pick up from the ponds, usually a frog or a toad, or

at this time of year as they leave the ponds after breeding, Palmate Newts. Of late, two Grey Herons have started to drop in at the ponds. They won't find

any fish but there's plenty of other wetland life in there to whet [wet?!]

their appetites.

In

2020, 21 of our nestboxes were occupied, 16 by Blue

Tits and 5 by Great Tits. This year the

uptake has been 22 boxes, with 17 used by Blue Tits and 4 by Great Tits, and

for just the second time, one pair of Nuthatches. We monitor the boxes for the British Trust

for Ornithology's Nest Record Scheme, and a fully qualified bird-ringing friend

comes over to ring the nestlings when they are big enough. At the time of writing, we don't yet know the

outcomes for each of the boxes, but there is no doubt that the success rate,

given the cold, very dry April and prolonged cool, rainy spell of mid-May will

have taken a toll as adults struggled to keep chicks warm and fed. Sadly, at the time of writing, the Nuthatches

have lost their four young likely due to the poor weather.

A

regular task is cleaning the seed and suet feeders to prevent disease, while

the clearing out and disinfecting of the nestboxes is

a once-a-year job after the breeding season is over. Boxes that aren't occupied by breeding birds

will more often than not be used for overnight roosting, with a consequent

accumulation of droppings which need removing. Replacing old or rotting boxes is another

annual task, but the actual making of the boxes provides hours of patient

pleasure, especially on a gloomy, wet or windy winter's day.

A clutch of Blue Tit eggs . . .

and five Blue Tit nestlings waiting for the next meal

|

Photos: Tim Davis |

30

NATURE NOTES NO. 4 - OIL BEETLES OUT AND ABOUT

With Tim Davis

This little creature - a male Violet Oil Beetle (Meloe violaceus, pictured left) - the first of the year, was crawling through grass in the garden on 9th March. The species is commonest in meadows and woodland in south-west England, with patches of distribution elsewhere mostly in western and northern Britain. It is flightless and can be found between March and June, in gardens usually on grassy tracks - which over the years have helped the beetle to spread to all corners of our wild garden.

The female Violet Oil Beetle (pictured right) is considerably larger (up to 32mm in length) than the male and has a distinctly plump appearance, laying several thousand eggs in a burrow. The resulting maggot-like larvae climb up to flowerheads and attach themselves, using hook-like forelegs, to ground-nesting female solitary bees. Once in the bee's nest burrow the larva feed on the bee's egg and pollen store. The larva pupates and spends the winter in the burrow, hatching and emerging as an adult beetle in the following spring. The beetle gets its name from the pungent oily liquid which it uses to defend itself.

With the loss of wildflower-rich grassland and heathland from large parts of our countryside, and with those habitats three now extinct species of oil beetle, seven different species of oil beetle remain in Britain and Ireland, the most common being the visually identical Black Oil Beetle, which also occurs in North Devon, including Lundy where it has been found in recent years as insect recording has become more popular. How can you tell the two species apart? Violet Oil Beetle has an indented thorax, while its cousin has a straight base to the thorax - the part between the head and the body in the photographs. The beetle will quite happily climb onto a hand if you're careful, allowing close-up views - but even then, a magnifying glass would help!

Photos: Tim Davis and Tim Jones

Watch out for ...

. . . the return of our spring migrants. Two of the first birds [both warblers] to return from winters spent in West Africa or the Mediterranean are Chiffchaff and Blackcap, both usually arriving from the second half of March into early April. The males of both species will very quickly set about establishing breeding territories in scrubby areas of blackthorn and bramble or thickets, often singing tucked away in branches of hazel, willow or hawthorn. If you are not already familiar with their songs, you can tune into them by visiting www.xeno-canto.org and typing their international English names (Eurasian Blackcap and Common Chiffchaff) into the search facility. Another useful tool which I always carry with me is the Collins Bird Guide app, available for both iPhone and android mobiles.

Chiffchaff [by Dean Jones]

Male Blackcap [by Richard Campey]

Recycled Wellies!

Thanks to all who dropped off old wellington boots at Harpers Mill. Their upperparts will be put to good use as (waterproof)] hinges for nestbox lids. More welcome at any time!

Tim

9

NATURE NOTES NO. 3 -

WINTER DAYS & EARLY BIRD SONG

With Tim Davis

With woodland on the slopes either side

of our house at the upper end of the Sterridge Valley, and numerous

berry-bearing trees and shrubs as well as regularly filled seed and suet

feeders around the garden, we are blessed with a wide variety of birds. One of

the great joys of midwinter is the 'start-up' of bird song, nearly always

kicked off in the second half of December by Great Tits and Song Thrushes, all

keen to establish territories well before the onset of nesting as winter gives

way to spring - which now happens two to three weeks earlier than when I was

growing up in the 1960s.

By February - assuming we aren't hit by

another 'Beast from the East' - Blue, Coal and Marsh Tits, Woodpigeons,

Blackbirds, Chaffinches, Siskins, Wrens, Dunnocks, Goldcrests, Treecreepers and

Nuthatches will also be singing in the surrounding woodland, along with one of

the shyest and most elusive of British birds, Mistle Thrush, their strident,

ringing song delivered in long bursts from the very tops of the tallest trees. Last year three pairs were 'broadcasting'

their territories in Woolscott Cleave (two) and Smythen Wood. While Blackbirds are renowned early

breeders, some even before the old year turns in milder winters, Ravens are

amongst the first to be feeding young in the nest. Already in very early January, as I write

this, our local pair are back on territory, while on sunny days we have watched

Buzzards and Sparrowhawks begin their aerial displays.

If we find ourselves in lockdown again

this spring, there's plenty of nature close to home in which to breathe and

lose yourself for regular mind-restoring periods.

Tim J and I found this little fellow (about 1cm long but

sadly dead) caught in a strand of a spider's web above the door to our cottage

on 30th December. One of a family of

pollen-feeding beetles commonly called False Blister Beetles, this nationally

scarce species, Oedemera femoralis, is nocturnal and feeds mainly on ivy

and sallow from April to September. The

Devon beetle recorder, Martin Luff, tells me that there are currently 40

records for the county, but this is the first for North Devon. The find was a reminder that during the past

year, due in large part to lockdown (no work and no travel!) and the warm and

sunny spring and early summer, we added all sorts of insect species to our

garden list. To find this one on the

penultimate day of the year was something of the icing on top of the Christmas

cake!

If you want to get into insects, one of

the best photographic guides is Paul D. Brock's A comprehensive guide to

Insects of Britain & Ireland, a new and expanded edition of which was

published in 2019 by Pisces Publications. We purchased our copy online at www.nhbs.com,

price £28.95.

Wanted: old wellies!

If you have old, worn-out or unwanted wellington

boots, I should be delighted to have them - the upperparts make perfect hinges

for nest boxes! All you need do is drop

them off either at the village shop for me to collect, or put them under the

post box at Harpers Mill. Many thanks.

Tim

Photo - False Blister Beetle, by Tim Davis

12

NATURE

NOTES NO. 2 - JAYS

with Tim

Davis

Writing this in the dying days of October, with autumn well

and truly under way and the annual rain of leaves gathering pace, jays have

suddenly become more evident in our Sterridge Valley garden. Normally a noisy but shy, almost reclusive

bird of mainly broadleaf, but also coniferous, woodland, these large colourful

members of the crow family take advantage of the abundance of food that nearby

gardens have to offer. They are opportunists, their omnivorous diet consisting

mainly of seeds, nuts and berries, but insects, small mammals such as voles and

bats, and eggs and nestling birds also feature on the menu.

Photo by Richard Campey

The jay's scientific name, Garrulus glandarius, is as

beautifully descriptive as the bird itself, the former meaning noisy or

chattering, and the latter referring to acorns, the food with which it is most

associated - in particular for its habit of burying acorns, as well as

hazelnuts and beech mast.

For a large bird, similar in size to a rook or carrion crow,

jays can be surprisingly difficult to see well, rarely moving far from cover. As Richard Campey's striking photo shows, the

jay's plumage is pinkish,

the wings black and white with a panel of distinctive kingfisher-blue feathers.

The head has a pale crown with black streaks and a well-defined black !moustachial'

stripe. Usually

it is the raucous call or the flash of a broad white rump that draws the eye.

This autumn we have enjoyed watching

the antics of up to four birds moving around the garden, collecting nuts and

burying them in the meadow for retrieval later in the winter. That not every

acorn or hazelnut cached is later collected and eaten is evident from the

numerous oak and hazel seedlings that appear across the meadow every spring.

The realisation dawns that the meadow, if not managed as such for its

wildflowers, butterflies and other insects, would quite quickly become a

woodland. The important role that jays play in woodland ecology thus also

becomes apparent.

Jays occur across most of the UK, with the exception of

northern Scotland. The current breeding population is estimated at 170,000

pairs [www.bto.org/birdtrends]. In some

years, typically when a good breeding season is followed by a poor autumn for

nuts and berries, large flocks may roam nomadically, covering great distances

in search of food.

9

NATURE NOTES NO. 1 - SABRE WASP

While walking the woodland trails of Woolscott Cleave during 'lockdown spring', it wasn't only birds that I was enjoying watching and listening to. Insect life too holds much fascination, though this often involves training one's eyes to look downwards rather than upwards!

One particularly startling - and beautiful - creature I came across in late June was a female Sabre Wasp (or Giant Ichneumon) Rhyssa persuasoria (pictured). The largest ichneumon in Britain - females can grow to 4 centimetres in length, plus another 4 cm for the needle-like ovipositor - it is also readily identified by the white spots along its black abdomen and its orange-red legs. Despite its fearsome appearance, it is completely harmless to humans and pets.

Adults can be encountered mainly in July and August, along woodland paths and clearings. They feed on sugars and starch obtained from honeydew or pine needles. Far from being a 'stinger', the ovipositor is used to drill deep into wood and lay eggs on the larvae of other insects, such as Wood Wasps, living within the timber, which become a food supply. The Sabre Wasp's larvae overwinter in the wood, pupating in spring and emerging as adults.

Sabre Wasps occur widely across Britain in mixed and coniferous woodland, such as Woolscott Cleave. Sadly, the specimen I encountered had evidently been in a tussle with a would-be predator, having lost several of its legs.

Tim Davis

31

WOOLSCOTT CLEAVE - Bursting with Wildlife

During the Covid-19 lockdown I have been walking the tracks of Woolscott Cleave - over the road from our home at Harpers Mill - on a regular basis, in part for much-needed exercise but also to monitor the continuing resurgence of wildlife since the felling a few years ago of all the larch trees (vectors of the fungal disease Phytophthora ramorum, also known as 'sudden oak-death') and the thinning of over-crowded conifers.

While the most obvious and immediate beneficiary of much of the conifer clearance was bramble, which quickly responded to the abundance of light after decades of dense shade, many of the open areas are steadily being colonised by broadleaved trees, especially birch, willow and hazel, along with oak, beech, rowan and especially sweet chestnut. Ash seedlings too proliferate but are unlikely to grow old owing to 'ash dieback', yet another new fungal disease that is gradually wiping out the UK's ash trees, with many of our local ash trees, including in Woolscott Cleave, showing severe symptoms, though there are hopes that a small proportion may prove resistant.

Woolscott Cleave in Early Spring [Tim Davis]

Mammalian life that I have encountered includes roe and red deer (including last autumn a rutting stag), with one recent sighting of a Sika deer (a Japanese native now widely dispersed in the UK and interbreeding with red deer), grey squirrel, fox, and signs of otter passing along the Sterridge River. One of the small spring-fed trackside pools annually has frogspawn, pondskaters and whirligig beetles. Wildflowers in the form of bluebells, primroses and red campion are increasing. On the downside, so too is the highly invasive Rhododendron ponticum, though efforts are being made to eliminate it before it gets a hold and begins to overwhelm the native vegetation. Time is of the essence, as a mature flowering shrub - though undoubtedly an impressive sight - can produce a million microscopic seeds annually. These drift on the wind to infest new areas, making removal an ever more daunting and costly prospect for landowners.

Along with butterflies (e.g. speckled wood, peacock, green-veined white and meadow brown), it is the birdlife that has really transformed the nature of a springtime walk around Woolscott, especially early in the morning when the dawn chorus is in full swing. Here's a list of the species known to be nesting in the wood this year: tawny owl (occasional day-time hooting denoting their presence), raven (one pair fledging three young), carrion crow, woodpigeon (many!), great spotted woodpecker (at least three territories), nuthatch (three pairs feeding young), treecreeper, great tit, blue and coal tits (the latter more of a conifer specialist so currently higher in number), chaffinch, siskin (at least two pairs), goldcrest (which sing, feed and nest mainly in conifers), many pairs of wren, dunnock, robin and blackbird all with fledged young, song thrush (two or three pairs, and fledged young being fed), and mistle thrush (males singing stridently from treetops at either end of the wood). Jays too are probably breeding this year.

Moreover, the presence of a greater number of warblers (all of them springtime migrants from African or Mediterranean wintering areas) markedly indicate the increased value of Woolscott for birds following the opening up of the once-gloomy conifer canopy. Chiffchaffs and blackcaps, the two earliest-arriving visitors in March, sing long and loudly in areas of birch, hazel, hawthorn and bramble (which provides perfect nesting cover), while three pairs of willow warbler (declining fast in much of southern England) sing mellifluously from the larger, more open areas of developing scrub, using the taller trees to feed on insects. It is also in these areas that a cuckoo has been present this year, singing its eponymous song sometimes into the late evening - only the third time we have heard (and finally seen) one in our 19 years at Harpers Mill. Other summer visitors that have stopped off in Woolscott on their way to breeding grounds elsewhere are spotted flycatcher and lesser whitethroat, the latter more commonly found in central and eastern England.

At one point a male crossbill - very much a conifer specialist, and an early breeder each year depending on seed availability - was coming to drink from the Sterridge at Harpers Mill, and later sightings of several birds over the wood suggested breeding may have taken place.

Woolscott Cleave also provides a winter home both for the resident birds and for woodcocks, which arrive in the UK from their Siberian breeding grounds 4,000 or more kilometres away. Very much a species in trouble, the director of the British Association for Shooting & Conservation (BASC) exhorted its members to forego shooting woodcocks during the winter of 2018/19 (annually some 80,000 are shot in the UK). Woolscott also provides night-time roosts for all or most of Berrynarbor's rooks and jackdaws outside the breeding season, mixed flocks of several hundred calling loudly overhead as evening gathers. At dusk in springtime too we have watched migrating swallows and house martins settle in the treetops to spend the night before moving on early the following morning.

The burgeoning wildlife at Woolscott Cleave shows what can happen when a dense, even-aged conifer plantation is partially

Female Blackcap [Richard Campey]

Willow Warbler [Richard Campey]

felled and thinned and natural regeneration (with some planting of broadleaf trees using native, local stock) takes place. To maintain - and further enhance - the variety and abundance of wildlife that has colonised the wood, ongoing careful management will be required. Self-seeding larch will need to be removed, while the mature nature of the remaining conifers (Douglas fir, western hemlock and Sitka spruce) means that opportunities to increase still further the proportion of native, wildlife-rich deciduous species will arise, whether through felling or windblow.

I'd like to thank John and Fenella for their continuing enthusiasm where Woolscott and its value for wildlife is concerned. I hope their desire to create a restricted-access zone where wildlife can get on with their lives largely free of human disturbance will be welcomed by all users.

Tim Davis

13

WHERE HAVE OUR GREENFINCHES GONE?

Greenfinch © Mike Langman

I sometimes get asked why

Greenfinches have disappeared from many of our gardens. Certainly in the 12

years that Tim Jones and I have lived at Harpers Mill we have noticed fewer

Greenfinches in and around the village, as well as at Smythen Farm. For some reason

Greenfinches are only infrequent visitors to our garden, despite lots of

apparently suitable habitat. Among several diseases which affect birds, one in

particular, trichomonosis, has been the principal cause of the decline in

Greenfinches, and to a lesser extent Chaffinches.

Trichomonosis typically causes disease at the

back of the throat and in the gullet. Affected birds show signs of general

illness, such as lethargy and fluffed-up plumage, and may show difficulty in

swallowing or laboured breathing. Some individuals may have wet plumage around

the bill and drool saliva or regurgitate food that they cannot swallow. In some

cases, swelling of the neck may be evident. The disease may progress over

several days or even weeks. It does not affect humans or

other mammals.

An item on the British Trust

for Ornithology's website in mid-September reported new research that brings

our understanding of the disease outbreak up to date.

The widespread emergence of

trichomonosis in 2006 has resulted in a substantial decline in the Greenfinch

breeding population. The new research demonstrates

that mass mortality in Greenfinches continued in 2007-2009 at a rate of more

than 7 per cent of the population each year, but with a shifting geographical

distribution across the UK. In this time the population of Greenfinches in

Great Britain fell from some 4.3

million to about 2.8 million birds. It appears that the disease jumped from pigeons or doves to finches, but

quite why Greenfinches suffered more than other small birds remains unknown.

For more information on

trichomonosis and other bird diseases, visit the BTO website at www.bto.org and

follow these links: home > volunteer-surveys >

garden birdwatch > gardens & wildlife > birds > disease. This will

take you to a page on 'Disease and garden birds'. Here you will find advice on

what you can do to look after your garden birds, especially the need to keep

feeders clean. If you would like to report finding dead garden birds or signs

of disease in garden birds, there is also an online reporting form.

Tim Davis

29

SAVING

SWIFTS

Most Berrynarbor residents will be familiar with Swifts,

which arrive in the

In addition, their

habit of [literally] screaming at high speed low over rooftops, often in small

parties, especially towards dusk, makes them unmissable to anyone out and about

the village.

Swifts are the most aerial of birds. They feed on flying

insects and never perch on wires like Swallows. In fact, once a young Swift has fledged, it

is unlikely to land anywhere until it reaches maturity and looks for a nest

site of its own three or four years later.

But finding that desirable location in which to nest is becoming

increasingly hard for Swifts. Their

nesting places, in the eaves of rooftops and older buildings with cavities,

such as the Manor Hall, are

disappearing as buildings are modernised and access to roof spaces blocked up.

Ten years ago, when Tim Jones and I came to live in the

Now, we have a chance to help them. As

some of you may have seen in a recent issue of the North Devon Journal, a

conservation project has been launched within the North Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty [AONB] to help Swifts. With funding from the North Devon AONB,

researcher Greg Ebdon has been visiting villages within the AONB to record the

numbers of Swifts and the location of nest sites, as well as looking for

appropriate sites where specially constructed Swift nestboxes can be put up. Four nestboxes have already been installed

at St Helen's Church in Abbotsham, for example.

If you would like to encourage Swifts to nest within the

eaves of your house or on the wall under the eaves, you can obtain a nestbox

from Greg by contacting him on greg_ebdon@hotmail.com. Note that because Swifts need height to take

off, single-storey buildings are not suitable; nest sites are usually located

at least six metres from the ground. Once

a nestbox has been installed, to stop other birds using it, the opening can be

blocked until the Swifts return. If you

are unsure whether your house is suitable, I should be happy to give advice. You can contact me on 882965 [daytime] or

883807 [evenings/weekends] or at tim.davis@djenvironmental.com.

Tim

Davis

For

more information on Swifts, including a short video and a sound recording of

their calls, visit www.rspb.org.uk/wildlife/birdguide/name/s/swift.

Artwork

by Mike Langman [www.mikelangman.co.uk]

32

THE

BIRDS OF LUNDY

Lying

some ten miles off the nearest point on the

We

- that is the Tims of Harpers Mill - have been visiting Lundy for more than 50

years between us. The idea to write a

new book on the island's birds first struck in 1999. Initially we contacted former Lundy Warden

Nick Dymond to ask if he had any plans to update his own book on Lundy's birds,

published by Devon Bird Watching & Preservation Society in 1980. At that stage Nick was part way through

revising the text but, as he put it, 'running out of steam' and with many other

things on his plate. Nick kindly forwarded his notes, giving us a

great starting point. In the intervening

years, as well as scouring every Lundy Field Society (LFS) Annual Report, Devon Bird Report and the surviving LFS logbooks

from the island, we have researched every scrap of information we could find.

This included a fascinating visit to the Alexander Ornithological Library in

Most

of the work has been done in our spare time, but, conscious of the years

passing by, we began to step on the accelerator in 2005 until finally, in

February this year, we completed the manuscript. Since

then we've been polishing it and adding bird records for 2007. We took the book to the printer, Short Run

Press Limited of

The

Birds of Lundy itself fledged on 29th September at a launch at RM

Young (Bookseller) in

The

goals we set ourselves in preparing the book were:

- To produce an up-to-date account of the ornithology of Lundy, with

a review of historical records and an account of all bird species that

have occurred on the island since the founding of the LFS in 1946 and the

commencement of daily records in 1947.

- To raise awareness of the Devon Bird Watching & Preservation

Society and the Lundy Field Society and promote their roles in the

research and conservation of birds and the natural environment, both in

Devon and on Lundy.

- To invest any proceeds made from sales of the book in bird-related

conservation work on Lundy.

- To promote awareness and appreciation of Lundy's conservation value

and its importance as a prime 'ecotourism' destination and birdwatching

venue.

- To stimulate enhanced recording of birds and other wildlife on

Lundy.

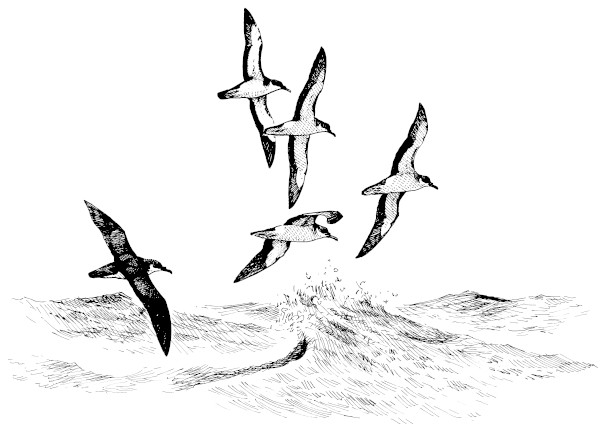

Manx Shearwaters by: Mike Langman

Whether

we succeed in all of these objectives only time will tell. The immediate result is a detailed account of

the 317 species that currently make up the Lundy bird list, plus a further 36

species which for various reasons do not qualify for the full list. Internationally renowned biologist Hugh Boyd,

who began his ornithological career as LFS Warden in 1948/49, has penned the

book's foreword. [Health permitting,

Hugh will be staying with us on the island this October.]

As

well as writing the book, we also published it on behalf of Devon Birds and the

LFS. Both organisations contributed

grants to cover the printing costs, and we are grateful also to several other

individuals and organisations that have supported the book financially. All are acknowledged within the books 319

pages, which are enlivened by 20 colour photographs and more than 100 line

drawings by

For

more information visit www.birdsoflundy.org.uk or contact us on 882965 [daytime]

or 883807 [evenings and weekends].

If

you have thought about going to Lundy but have yet to do so, we hope that The Birds of Lundy might inspire you to

step onto the island boat, MS Oldenburg, and off at the other end onto the

Tim

Davis & Tim Jones

Manx Shearwaters are breeding on Lundy in increasing numbers following eradication of the rat population.

17

A RARE BUTTERFLY IN THE STERRIDGE VALLEY

Large Tortoiseshell Butterfly at Harpers Mill, 17th April 2003

We have been recording all kinds of wildlife in our garden at Harpers Mill over the past two years. On Maundy Thursday [17th April] this year, as we stood at the top of our drive waving off some visitors, a butterfly flew past that we immediately recognized as something different. Fortunately, it settled and basked in the sun on our rockery, allowing a careful approach to within 1-2 metres but always flying off fast and strongly if approached too closely, before returning to a sunlit area. We identified the butterfly as a Large Tortoiseshell, a distant relative of the familiar Small Tortoiseshell, that we recognised from time abroad, but knew to be very rare in this country. Fortunately, we were able to take three photographs at pretty close range, which have proved good enough to confirm the sighting. After basking for some minutes, the butterfly flew off down the valley.

The Millennium Atlas of Butterflies in Britain and Ireland, published in 2001, shows how Large Tortoiseshells used to be quite widespread but declined in the 20th century to become officially extinct as a breeding species. The Atlas says: "The few genuine sightings in recent years are thought to be mainly of individuals that have been reared in captivity from larvae obtained abroad and that have either escaped or been released into the wild". It also shows that the last record of Large Tortoiseshell in the Berrynarbor area was more than thirty years ago. We sent details of our sighting, along with the photographs, to the Devon branch of Butterfly Conservation, which featured the butterfly on the front cover of their county newsletter. The record is also being submitted, through the Devon Butterfly Recorder, to the Devon Biological Records Centre.

This was the first sighting of a Large Tortoiseshell in Devon for many years. We'll never know if it was a truly wild migrant from the continent, one which hibernated over the winter, or a butterfly that was bred and released in the UK. Interestingly, as everyone will recall, the week before Easter was unusually sunny, which may have played a part. Whatever, its appearance in our garden was very exciting and goes to show just what can turn up when you garden with wildlife in mind. In the last six months alone, we have recorded more than 150 different kinds of moth - many of them very striking and colourful. More about them in a future issue!

Tim Davis and Tim Jones - Harpers Mill

29