Rural Reflections

Covering ponderings and all things rural in North Devon.

by - Steve McCarthy

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 106

According to Google the meaning of the word aspire is to direct one's hopes or ambitions towards achieving something. This definition led me to question whether the word applies to everyone. After some consideration I came to the conclusion that it depends on the extent to which the word is interpreted. Personally, I know many people who do not regard themselves as ambitious, something that I feel is a direct consequence of us living in a culture where the word is linked to one's work status. Yet if, for example, a person has a disability [employed or otherwise] which impedes them from doing everyday activities, then aspiring to successfully carry out day-to-day tasks can be regarded as an achievement; and having lived with epilepsy all my life. I feel I have some background knowledge on the subject. But I digress . . .

Google's definition of the word aspire also led me to consider people in society who do good deeds for their fellow citizens - something that the pandemic has undoubtedly brought to the fore. The more I contemplated this, the more it seemed to me that such people fall into two groups; those who are somewhat conceited and boastful and those who are modest and humble. Although I feel the former group are a minority in our society, I have, unfortunately, come into contact with quite a number of people who aspire to seek the highest mountain top to tell their stories of great deeds to anyone who is willing [or not] to hear them. Such proclamations are, I feel, for two reasons. Firstly, they enable the person's alter ego to swell to an even larger size than what it already is, but more significantly, it allows them to receive as much gratitude as is possible from all those connected with the good deeds they undertake.

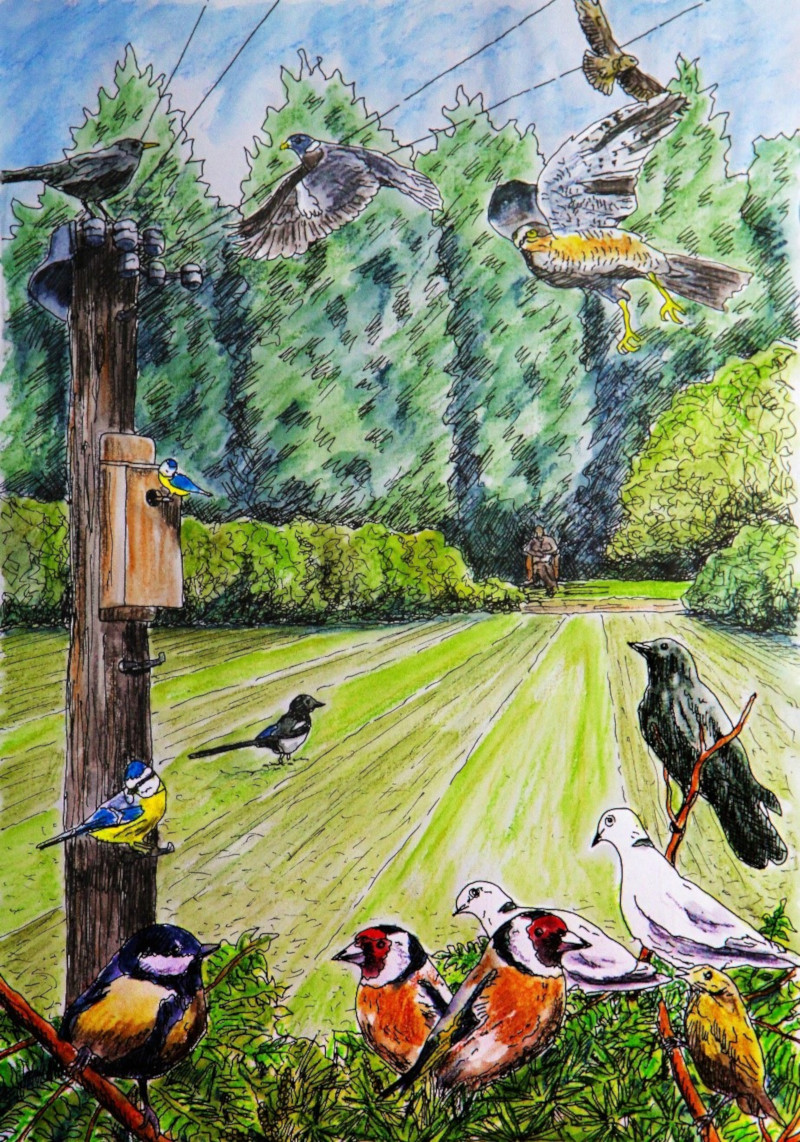

To me, this is the key difference between these people and those who are humble and modest; for this latter group do not carry out their good deeds with the intent of seeking praise. [It is important to remember, however, that it is acceptable to receive praise when it is given rather than bat it away.] There is one such 'person' who I know that is modest, giving pleasure to everyone all year round - or at least to those with whom they come into contact - and never expect gratitude: our natural world. However, that is not to say there are those of us who give thanks for the beauty of nature in our own way whether it be through prayer, meditation or whilst in direct contact with our natural surroundings; and whilst our countryside may not expect obligatory praise for the contentment and satisfaction it provides, it would do us no harm to at least give nature the respect it deserves, rather that inflict any further damage upon it. One can only live in hope that as a society we have culturally reached a turning point to recognise the past consequences of the damage already inflicted upon our natural surroundings.

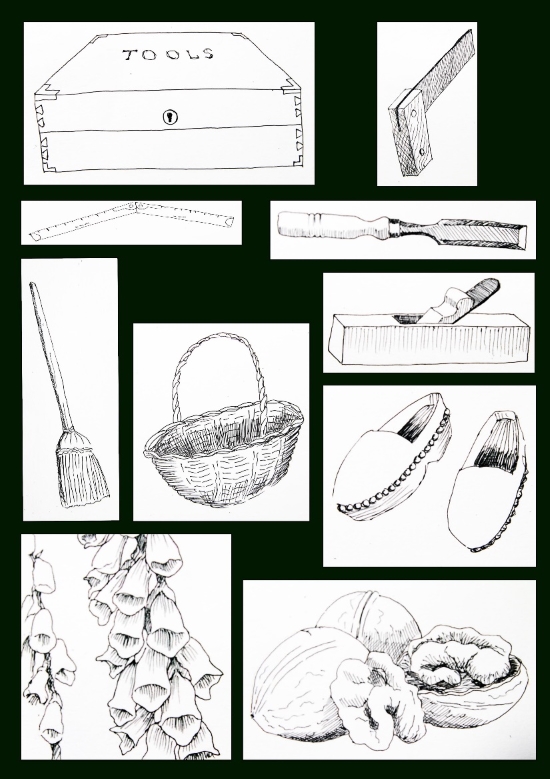

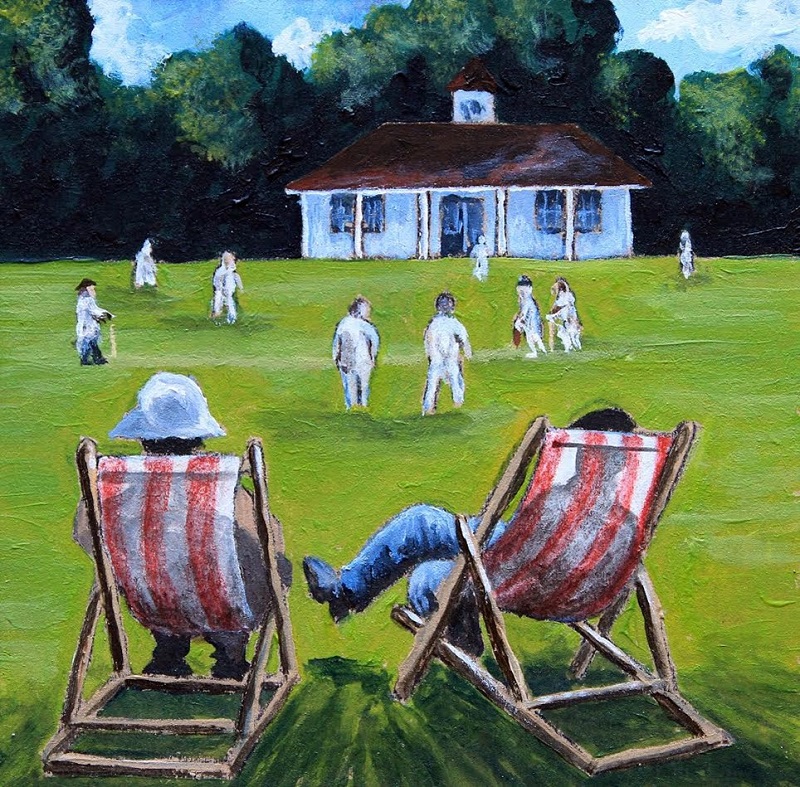

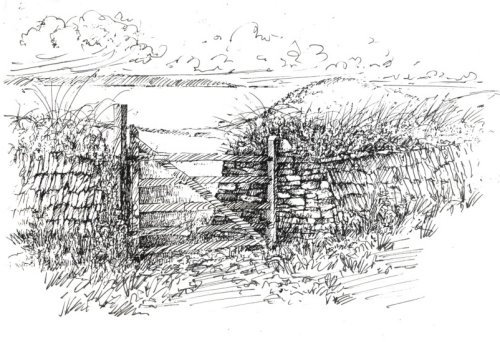

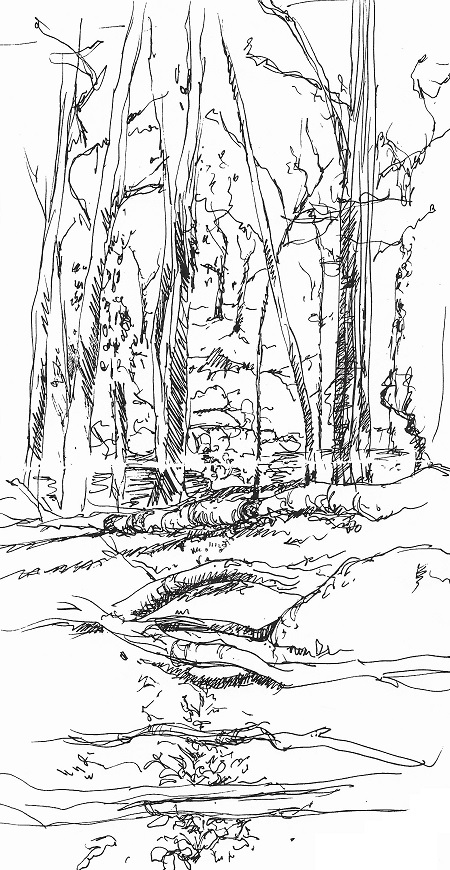

But back to the subject of praise; and, more significantly, the fact that this will be my last Rural Reflections article and so time to say thank you to all those who have helped, contributed towards and encouraged me to write over 100 articles during the last twenty-two years. Firstly, you the readers, and not forgetting those who have passed away, without whom there would have been no articles; your positive comments have made me feel that my efforts to devise and compose my contributions have been worthwhile. Secondly, to Paul and Debbie who have produced wonderful illustrations [often at short notice!] to accompany my articles. Thirdly, my husband Dean for typing up 106 articles, the fingers of his two hands being somewhat quicker on the keyboard than the index finger of my left hand and thumb on my right hand [the latter only used if a capital letter would have been required!].

And finally to Judie, especially for her bi-monthly nagging [her word, not mine] for another submission. Judie, there were times in the past when I wondered if I should call it a day. But it was my loyalty to you and my admiration of your dedication to this newsletter that kept me going and ensured another article was forthcoming. So, from Dean and myself, a huge thanks for all the effort and unrelenting hard work you have given to the Berrynarbor Newsletter over the past years.

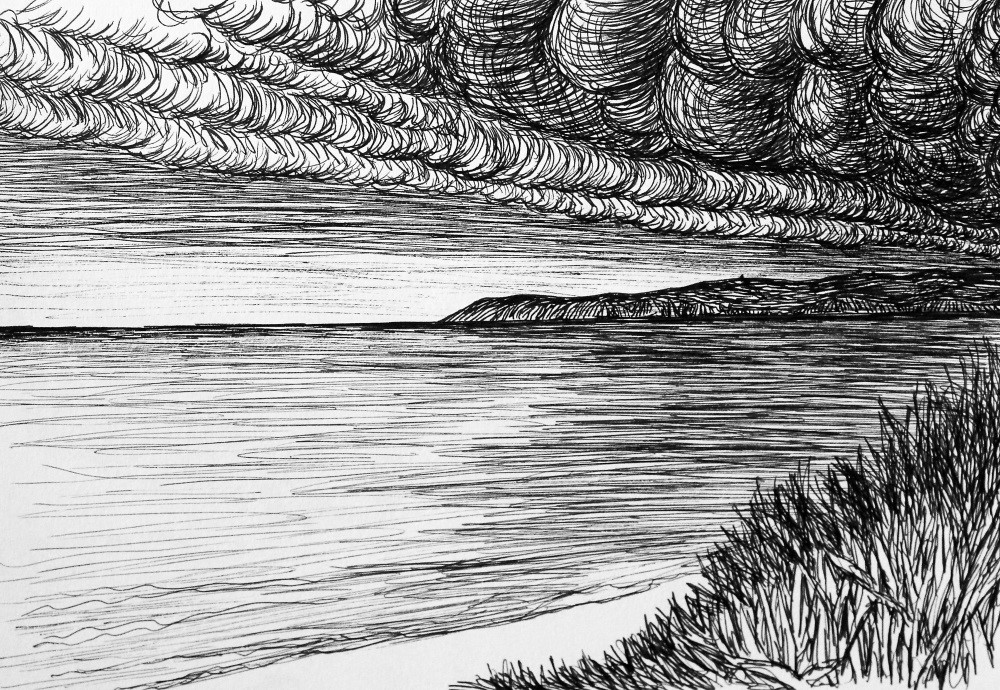

Illustrated by: Paul Swailes

Steve McCarthy

29

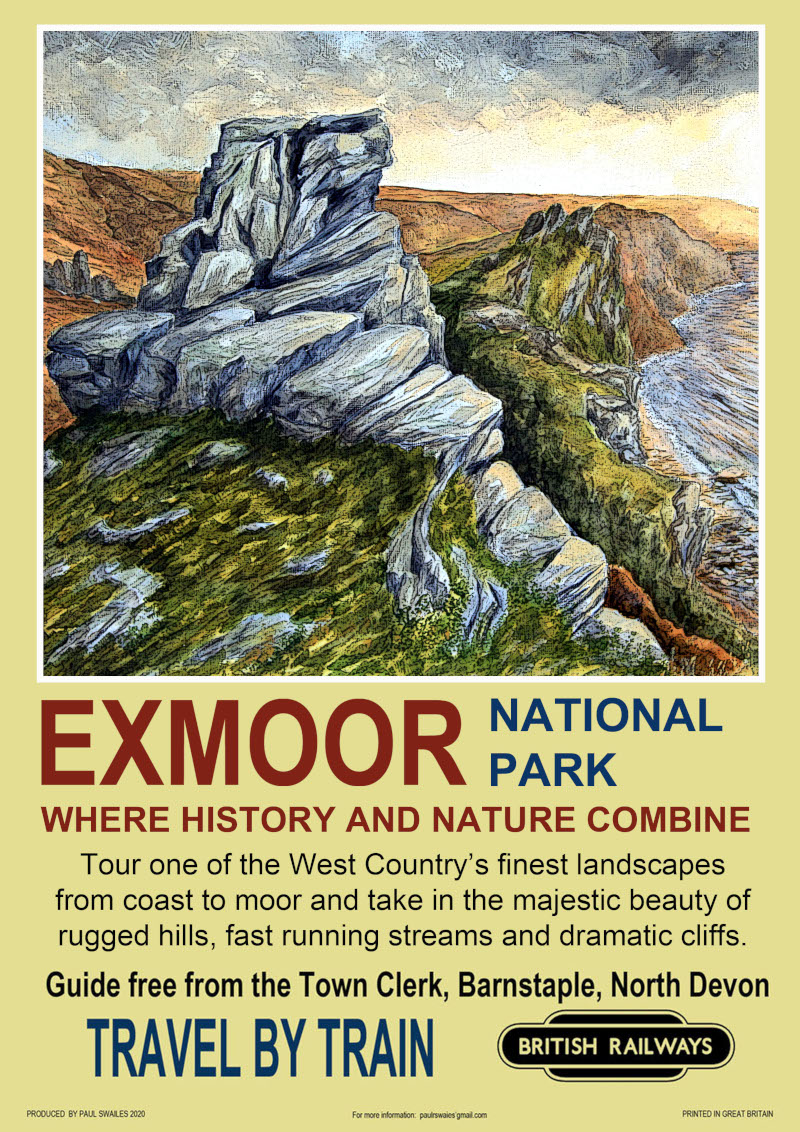

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 105

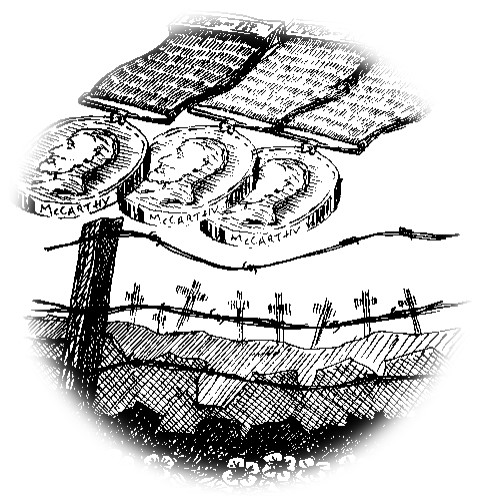

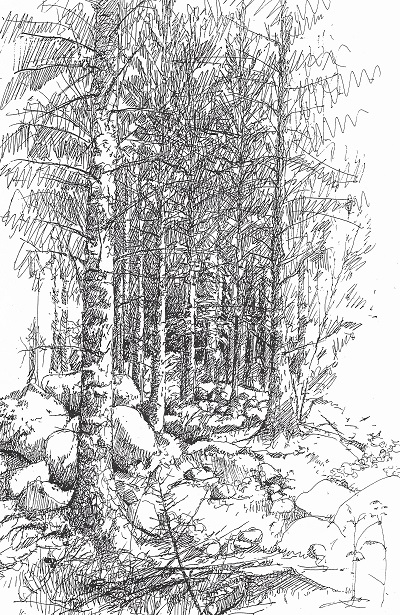

Nigel Stone was Chief Executive at Exmoor National Park Authority for eighteen years from 1999. A keen photographer, he spent much of his leisure time capturing the moor's stunning and varied scenery. It was a pursuit that would eventually lead to a ground-breaking publication, Exploring Exmoor from Square One. In his book, Stone divides the National Park into a matrix of numbers and letters so that each square can be cross-referenced with accompanying pictures and text that highlight something of interest. By the end of the book the reader is left enriched with Stone's bountiful knowledge of Exmoor. For example, square K13 refers to a close-up image of the replacement for the original Cussacombe Post, erected to commemorate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. Stone explains the original post was replaced in 1977, the year of our current Queen's Silver Jubilee and that a plaque was installed for her Diamond Jubilee. (I wonder if another will be attached for her Platinum Jubilee?)

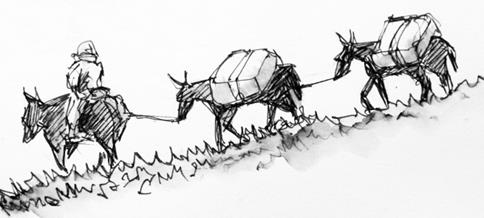

Stone also mentions place names that reflect an Exmoor before roads, such as Sandyway, lying halfway between Withypool and North Molton, perhaps its unsurfaced track connected the two villages? There are pictures too of Exmoor's fords and packhorse bridges which take one back to a time before the motor vehicle. Going much further back in our history, Stone alerts the reader to enclosures on Exmoor that date back to the late Neolithic period and shows where monuments, cemeteries, barrows and cairn remains from the Bronze Age can be found. Within Exmoor's boundary there is also an Iron Age promontory fort as well as a fortlet believed to have been built in 50AD, seven years after the Roman invasion of Britain. Further evidence of Roman occupation on Exmoor includes archaeological investigations at Sherracombe Ford and sediments found on Anstey Common.

Stone contemplates a battle that may have occurred between the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings at Wind Hill and shows where the Normans were present on the moor; forever keen to protect their land from invasion, the outline of a motte-and-bailey castle can be seen near Parracombe. Further west, on Exmoor's boundary, there is clear proof above ground of Combe Martin's mining history, with records showing that activity first occurred in the late thirteenth century. Clue's to mining within Devon's Exmoor can also be found near Heasley Mill which is thought to date back to the fourteenth century. Moving into medieval times, Stone provides evidence of deserted settlements and mentions Holywell Bridge, the origins of its name thought to have derived from the nearby site of a holy well. At North Furzehill, meanwhile, there are the remains of a ruined building which is part of a medieval mill.

Confirmation of our ancestral farming is littered across the moor.

In his book, Stone provides pictures of field patterns created as a result of the eighteenth and nineteenth century Inclosure Acts. He also shows early nineteenth century farmhouse remains and refers to place names such as Butter Hill which, he suggests, reflect the richness of the area for past grazing. He also mentions past engineering work such as the Payway Canal and Warren Canal, both partially built and which start close to the man-made damn, Pinkworthy Pond. Heading north-east from the damn towards the coast one begins to discover deep elongated cuttings into the earth, embankments, bridges and lines of scrub, all acting as historical reminders of the Barnstaple to Lynton railway line. In operation between 1898 and 1935, a reminder of its service within Exmoor National Park can be spotted at New Mill in the form of a dysfunctional and seemingly out-of-place railway bridge.

The running of the line spanned the years of the First World War, with Exmoor offering its own timely reminders by way of coastal gun emplacements. Meanwhile, several areas on the moor were used for military training during the Second World War, including Brendon Common where the remains of 5-inch rockets have been uncovered.

If you have an interest in our National Parks then Exploring Exmoor from Square One is undoubtedly a book for you. For it does not just refer to its layers of history, Stone also talks of the flora, fauna, woodland, landscapes, villages, night skies and, of course, its ponies. His aptitude for photography is also reflected in the quality of his pictures which, in my opinion, define the book as one that can be comfortably perused whilst enjoying a hot drink. My overview of the book only skims the surface of its content. What's more, I have ensured that the number of place names to which I make reference are limited; however, a keen observer may have noticed that these places are all in Devon, an area that accounts for only one third of Exmoor National Park. The other two thirds lay within Somerset, so to discover the wealth of information Stone provides across the border, you'll need to get hold of a copy!

Having chronologically outlined some of the historical evidence that the book features, I should like to conclude this article with three sites that have either an unknown origin or involve legend and folklore. Firstly, the two standing stones on Lyn Down which, as a result of being moved from their original location, now means that their origins are unknown. Then there is Mole's Chamber, its name derived from the legend of Farmer Mole who, along with his horse, entered the mire and disappeared into the bog. Finally, there are the earthworks at Shoulsbury Castle which, according to folklore, was held by King Alfred in a battle against the Danes. A more popular opinion, however, is that the earthworks date from the Iron Age - but personally, I always prefer a good old folklore tale!

Artwork: Paul Swailes

Steve McCarthy

20

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 104

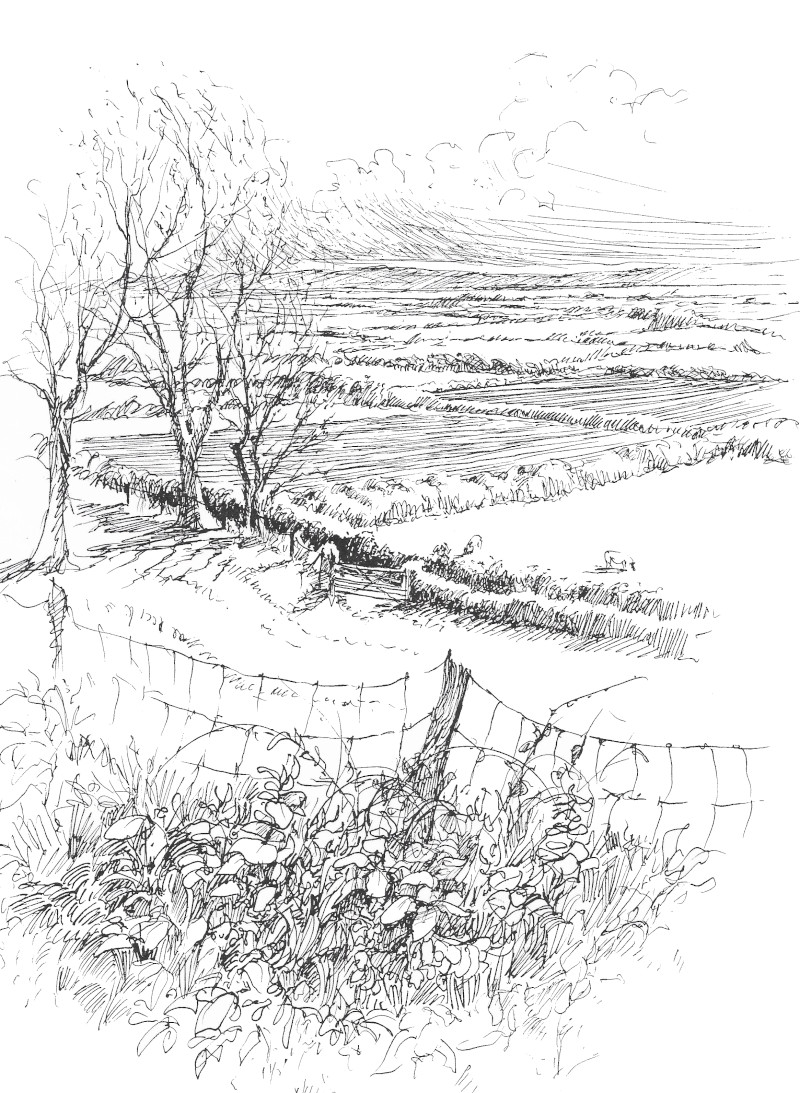

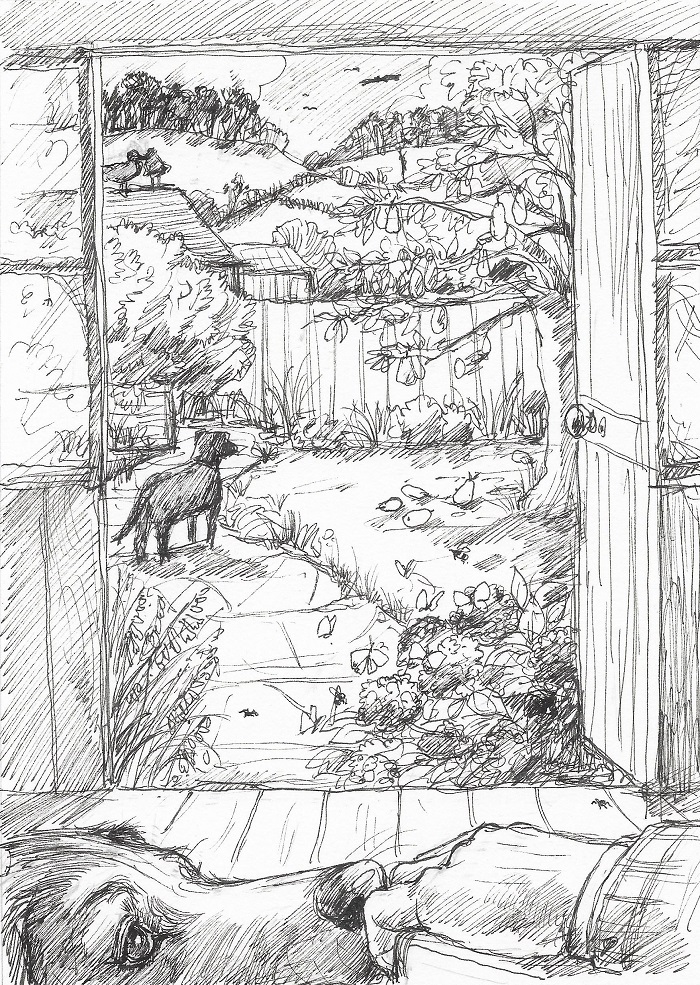

I am sat at my writing desk considering the composition of this article. As I do so, I rest back in my carver chair, gaze out of the window across the valley and look for any seasonal changes in the steep woodland on the far hillside. Tiny raindrops are falling, barely visible to the naked eye yet frequent enough to dampen the ground. Although my outlook is northerly, I can sense a low sun in the southwest sending rays too weak to cast shadows but strong enough to create an arched spectrum within the valley. In turn, I find myself singing, "There's a rainbow 'round my shoulder; And a sky of blue above; Oh the sun shines bright, the world's alright; 'Cos I'm in love"; lyrics from a song by Al Jolson, featured in the 1928 film, The Singing Fool. Seven years previous to this film, Jolson had first sung another weather-related song, one with lyrics very appropriate for the timing of this issue: "Though April showers may come your way; They bring the flowers that bloom in May."

Of course, it not just our flowers that interact with rainfall, for water is the lifeline for all of our natural world. The lives of humans, too, have been dictated by the presence of rain over thousands of years. For example, geologists describe the solvent action of rainwater upon limestone areas as 'the birth of preferential pathways'. Put simply, as water droplets are sent across the surface of limestone, so they begin to etch out the course they take. These minuscule corridors then create shallow channels, which in turn attract the flow of subsequent water. As each season passes, so it provides its own unique quantity of cloudbursts, each ensuring that these infant fluid passageways become more scored into the rock. Eventually a hairline crack emerges which over time develops into runnel, equivalent to a small stream or brook. This finally causes the ground to fracture and, as it widens, so a clearly defined escarpment, a hollow with sloping land on either side, emerges.

In global areas such as the West Bank, where limestone is a major surface formation, these large scale fissures, long narrow openings caused by the splitting of rock or earth, often play a major role in the development of footpaths. Guided by these pre-configured habits upon their terrain, early humans and their animals became dependent upon these clearly defined routes - routes which had evolved over time from the simple fall of water droplets.

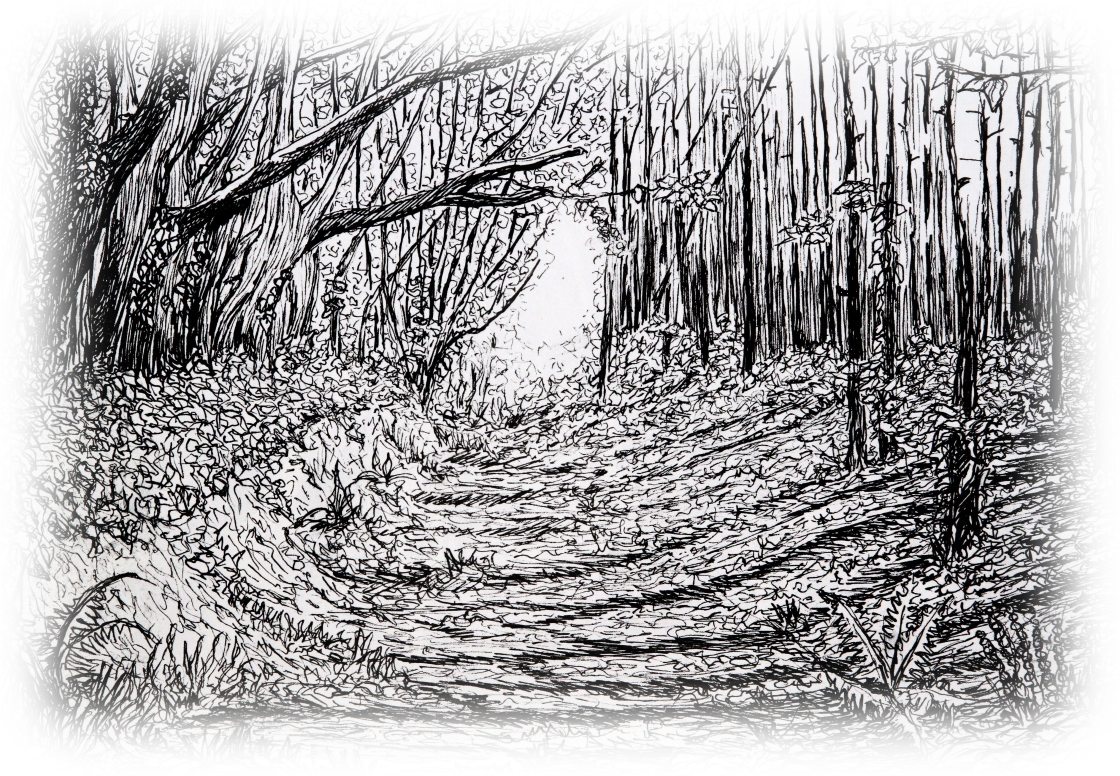

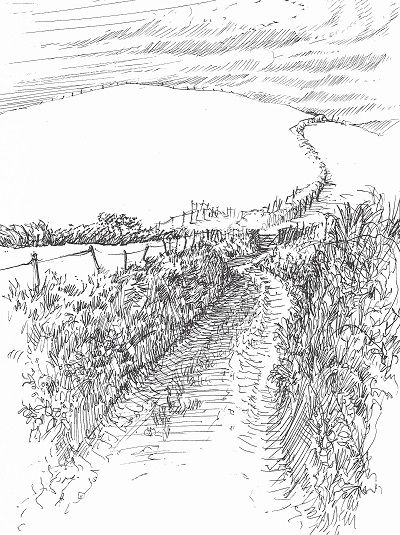

In a similar vein many of our own soft-stoned counties are webbed with holloways, a word derived from the Anglo-Saxon 'hol weg', referring to a sunken path that has been grooved into the earth over centuries, first by the weather and then the passage of feet and cartwheels. With many now over twenty feet deep and hidden beneath brambles and nettles, the author Robert McFarlane decided to seek out the holloways around the village of Chideock in Dorset with a close friend. Recalling these adventures in his book The Old Ways, McFarlane tells how they discovered fascinating stories associated with many of the passageways; tales of sixteenth century recusants taking refuge from persecution, of priests holding Masses in the seventeenth century and of fugitive aristocrats seeking shelter from twentieth century pursuers. McFarlane describes how the holloways felt active and co-existent, 'bringing discontinuous moments into contact' with them.

Two years later, his friend died young and unexpectedly. Four years on, McFarlane returned to the area and found himself unintentionally venturing along the same holloways, walking where they had cut sticks from holly bushes and camped out at night in adjacent fields. As he did so, he experienced startlingly clear glimpses of his friend, regularly seeing him at the turn of a corner or ahead of him on the path.

In the book, McFarlane later makes reference to W.H Hudson's A Foot in England, in which Hudson describes an experience whilst walking along the coastline of the Norfolk Broads during an exceptional low tide. Watching herring gulls whilst far out on the beach, he observed the beginnings of a 'soft bluish silvery haze' which caused the sky, sea and land to 'blend and interfuse' so that it produced what he called a 'new country', which was 'neither land nor sea.' Hudson interprets his experience as mystical - 'a metaphysical hallucination brought about by material illusions'. To him, the gulls temporarily appeared as ghost gulls; spirit birds that merely 'lived in or were passing through our world'; rather like McFarlane's encounter when seeing his close friend who had died four years earlier.

McFarlane refers to Hudson's 'new country' as somewhere we feel and think significantly different and imagine such transitions, which he has experienced himself when walking, as 'border crossings'. He adds that they do not, however, necessarily correspond to a change in the weather, climate, terrain, boundary or surrounding landscape.

I can relate to McFarlane's connection within invisible border crossings as it is something I have also encountered whilst traversing the countryside. For example, rambles upon the Cairn would often provoke a halt in my steps as I chanced upon a sudden change in atmosphere - despite there being no immediate alteration to my wooded surroundings. From recall, all these experiences aroused a warm, comforting sense of security at a mental, physical and spiritual level.

Yet other rural vicinities have induced cold and unwelcoming emotions, even a sense of morbidity. I can still vividly bring to mind one such area which was close to where I lived at the time. The area's terrain was flat and comprised a network of lush green fields, all bordered by low hedges with some dotted by sheep. A farmhouse, its accompanying barns and two bungalows were accessed by the minor road that dissected the land along with two footpaths - neither of which I felt inclined to trek; just driving across the landscape brought a shiver to my spine, such was my desperation to vacate a zone that felt bleak and sombre, no matter what time of year.

A little over twelve months after moving to the area, I was chatting with a neighbour who I discovered was a local historian. Having first regaled tales of the hamlet in which we lived, he then broadened his knowledge to the surrounding locations - including a notorious bloody battle that had taken place during the English Civil War upon the precise land where the fields, buildings and country road were now located. It is no wonder I experienced such negative vibes.

Yet not all ground connected with death need provoke an unwelcome reaction, especially when the bodies decaying beneath lay within hallowed earth; for solace can indeed be sought in many a graveyard, particularly at this time of year when their coniferous trees are blossoming or coming into leaf and their spring flowers are in full bloom. This sense of retreat and safety was perhaps best portrayed by the clergyman and author Richard Warner who wrote a number of topographical books, including A Walk Through Some of the Western Counties of England. Whilst traversing Exmoor, he came across Culbone Church and its accompanying churchyard, the latter to which he found himself being more drawn. After consideration, he concluded that the churchyard provided an 'indulgence of meditative faculty' to the extent of leading one's 'mind to thought' and soothing 'their brow to tranquility'.

Living, as we do, in these troubled times, I feel we all need a special place, be it inside or outside, where we can seek such inner peace and contentment. Happy Easter.

Illustrated by: Paul Swailes

Steve McCarthy

28

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 103

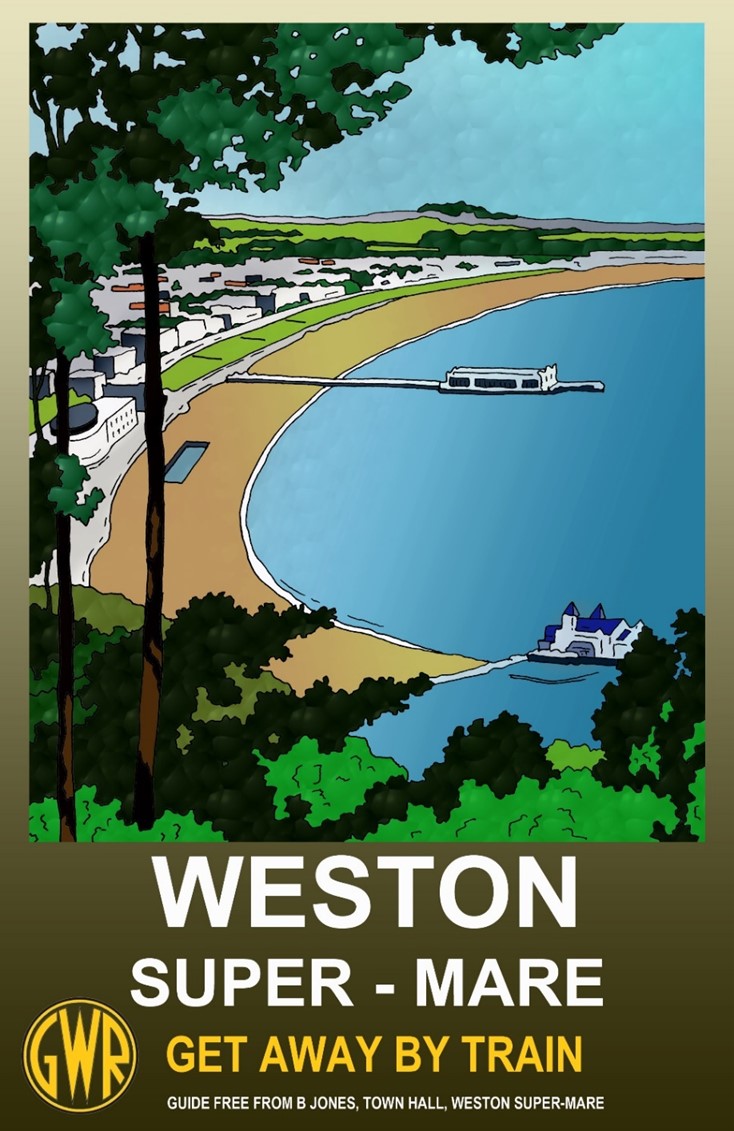

In my 100th article I reflected upon the material I had covered in previous contributions and, in so doing, found that they fell into distinct categories. For example, whilst some were about wildflowers, insects or trees, others related to the seasons or the weather. Another topic was also featured, albeit unintentionally, when I realised that the last twenty-plus years since that first offering have also followed me, quite literally, through the course of six property moves. The first was our move from Brighton to Ilfracombe in 2000 and then ten years later a brief stay in Combe Martin before heading to Riddlecombe. Just over twelve months later we upped sticks again, this time to Yelland. An unexpected job loss led to a further move to Weston-super-Mare within eighteen months.

The reasons for our move away from North Devon - and sacrificing as a consequence living in rural surroundings - have been mentioned in previous jottings, but for the relevance of this article it is worth recapping the three main reasons that led to our move to Weston. Firstly, we were specifically looking at locations along the M5 corridor where we felt there would be better job opportunities. Secondly, we had both previously lived in large conurbations and felt confident we should be able to adapt back to an urban lifestyle. But, most significant of all, we adore the Art Deco period with its unique architecture and decor - and stepping into the bungalow that we found was like entering a time warp back to the 1930's.

However, despite finding what we thought was our ideal property, it did not turn out to be our forever home. On reflection, the appeal of the bungalow perhaps outweighed its location, for it is fair to say we did not do our research. For example, we failed to acknowledge that the fields of the Somerset Levels are "what they say on the tin", dead flat, and in our view, lacking in character. As time progressed, we began to realise how we had come to take for granted North Devon's rolling pasture. So, with a strong yearn to once more live within a scenic rural environment, we placed our bungalow on the market. This time though there would be no swift exchange of contracts, for we had learnt the vital importance of spending time doing one's geographical homework. What's more, unlike our move to Weston which was driven by a desire to be close to the M5, this next search was to have no boundaries. And so, over the next eighteen months our quest for a new home took us as far north as Worcestershire and down as far as Cornwall. We excluded North Devon as we have a philosophy that one should never move back.

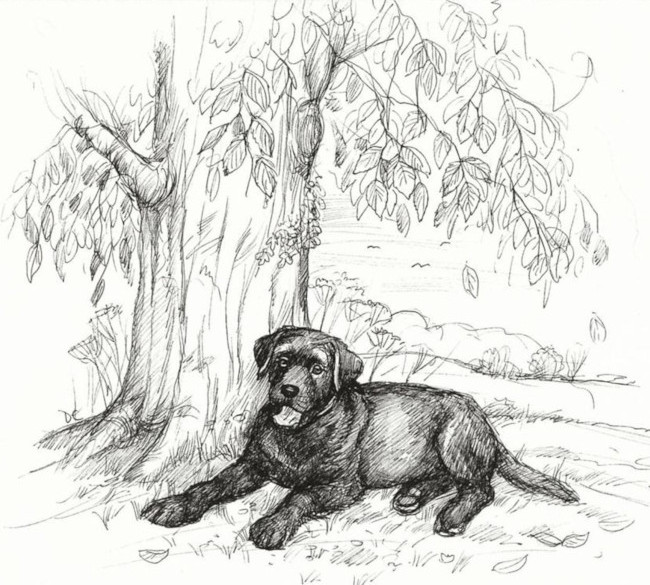

Like anyone else seeking somewhere to live, we had certain specifications that we hoped both the property and the location would meet. To our joy Brown Bracken, situated just on the outskirts of Minehead, ticked most of the boxes. It was in a rural setting without being remote; the lounge has an open fire; amenities are close at hand; it has a good-sized back garden for our three Labradors; local dog walks are in abundance; the bungalow has character [including a serving hatch - so handy!]; and the kitchen had the facility to have Aggie - our Aga - reinstalled. But, most important of all the bungalow and its location provided the three essentials that our Art Deco paradise could not offer. Privacy, tranquility and an outlook.

These three specifications were to pay valuable dividends for me personally when, twelve months after moving, my life would temporarily go on hold. Thankfully, my mental shut down was very short lived - just three weeks - but I am certain it would have lasted longer had I not had the environment in which I now live to recuperate. It is hard to put into words what actually happened. I can only say that it felt as though my brain had pulled down its shutters and placed a notice saying "closed until further notice"; and just before doing so, it sent a message of warning to my body: "Your adrenaline tank is empty. Refueling can only commence with rest and relaxation. Until then, you will be unable to give of yourself to others." To give an example, I could not even face talking to people. Sending text messages to friends and family was as much as I could cope with, and did indeed help, offering as they did kind words of comfort and advice.

Illustrated by: Paul Swailes

Interestingly it was suggested to me by more than one person that a daily walk would be beneficial. But even that felt too much. Something inside me said that I needed to just stay within the comfort of my own home where I could receive the support of my husband and to be able to rest and relax. As the days passed by and after many hours of sleep, I felt ready to venture outside and potter in the garden. This pottering, however, was continuously curtailed by the need to take breaks; not because I felt exhausted but because I just wanted to take in my rural surroundings. Often, I would sit indoors looking across the valley to the woodland and gorse on the southern slopes of North Hill, located on the northwest border of Exmoor. I would appreciate too how St Michael's parish church and its surrounding cottages nestled into the hillside, adding the perfect accompaniment to the vista - rather like Berrynarbor. I also spent many an hour sat beneath our veranda enjoying the array of birds as they flew back and forth from either the cotoneaster bushes or the magnolia tree to the feeders.

It was during this time that I took the opportunity to reflect upon the cumulative events that had led to my mental exhaustion. It also reminded me how fortunate I was to be living in such an ideal setting. But, most of all, it made me realise how I had taken my eye off the ball; rather ironic when one considers that the move to Brown Bracken had initially encouraged me to just sit and take in all that was around me. But during the summer and early autumn of last year, a busy social schedule amongst other things meant that I just did not relax as much as I should have. I am reluctant to say could not, for I feel that can often be used as an excuse. Ultimately, despite all that was going on at the time I could have still ensured that I took time to sit and just be.

At the time of writing this article there appear to be changes afoot with the weather. Gone are the wet, gloomy days of December and early January. For the third consecutive day the skies are cloudless so that when I look out of the window at seven o'clock in the morning and then do so again at half past four, I can sense once more how daylight is very gradually on the increase. It acts as a reminder of how this extra daylight will benefit our gardens, pots, window boxes, allotments and our surrounding countryside in the weeks and months to come; and this year I am going to ensure I do not miss an ounce of it. For making the time to sit and enjoy the very moment is so important for our wellbeing.

Steve McCarthy

34

RURAL REFLECTIONS -102

Britain has two breeds of sheep that can be regarded as truly primitive, one found in the far north of the British Isles and the other by the south coast. Both are still in existence as a result of being on land surrounded by water, the North Atlantic and the English Channel respectively And, whilst one area of land is due to the creation of a natural phenomenon, the other is a result of a manmade structure built, ironically, without the sheep's survival in mind. These two primitive breeds came to Britain by different routes, the northern short-tailed from central Asia via Scandinavia and Russia, whilst the long-tailed Celtic is believed to have come from the Near East before travelling through the Mediterranean countries.

The

long-tailed Celtic breed, whose sheep are tanned faced and horned, reach as far

back as the Iron Age. Its forbears once grazed across the heaths and downs of

the southeast as well as the countryside of south western England. Sadly,

crossbreeding down the centuries led to the breed disappearing from mainland

Britain. It was to their fortune, however, that the natural formation of a

shoal, in this case a shingle bar that rolled landwards, would guarantee this

ancient breed's immunity from surrounding influences. The shingle bar I refer

to is Chesil Beach, with the breed becoming more commonly known as Portland

Sheep.

The

long-tailed Celtic breed, whose sheep are tanned faced and horned, reach as far

back as the Iron Age. Its forbears once grazed across the heaths and downs of

the southeast as well as the countryside of south western England. Sadly,

crossbreeding down the centuries led to the breed disappearing from mainland

Britain. It was to their fortune, however, that the natural formation of a

shoal, in this case a shingle bar that rolled landwards, would guarantee this

ancient breed's immunity from surrounding influences. The shingle bar I refer

to is Chesil Beach, with the breed becoming more commonly known as Portland

Sheep.

Portland

has been a royal manor since before the Norman Conquest and a considerable

sheep run for much longer, factors that made the breed unique and famous throughout the kingdom for centuries. Able to

live on the island's sparse pasture, the

breed has a strong constitution that gives

it a strong resistance to disease and

parasites. This is a proud and independent

breed with a keen sense of its

own identity. The sheep demand respect and

are not easily intimidated, resulting in

a blase attitude towards sheepdogs. One other key characteristic of the breed

is its ability to lamb out of season, although unfortunately they barely

average one lamb per ewe.

During the nineteenth century, its pastural ground

was gradually eroded by commercial quarrying, leading to the breed eventually

disappearing from the island when the last flock was sold in 1913 at Dorchester

Market. By 1953 only a few flocks remained in Britain, with Calke Abbey

having the largest.

Even these sheep, however,

are no longer considered pure as over the years they have received

infusions of blood from other breeds, notably the Exmoor Horn.

Today, the breed's nearest descendants are the Dorset and Wiltshire

Horns.

However, in 1793 the crofters were warned by Sir John Sinclair, the first President of the Board of Agriculture, of their change of emphasis towards profit making. In his view they were no longer concerned for agriculture despite it being 'in every county the first and foremost of the arts'. Furthermore, he cautioned that if ever the manufacture of kelp should fail, it would 'bring certain ruin upon the tenants and their families'. He was to be proved right. By 1832 the price of kelp had collapsed, leaving the islanders facing destitution and at risk of famine. As a result, Traill's grandson, then laird, and his agent came up with a radical plan. Rather than encouraging the inhabitants to emigrate to larger, less populated islands, they proposed the building of a dry-stone dyke,12 miles in length, which would run the island's whole perimeter. It would also be tall enough to exceed any high tide and keep the sheep away from the island's cultivatable land. Only ewes were to be allowed in the fields at certain times of year, between lambing in mid-April and weaning in late July or early August. Other than at these times the breed has, ever since, been confined to the foreshore.

Illustrations by: Paul Swailes

They have, as a consequence, become an unusual breed. Whereas normal sheep eat by day, these flocks will also eat at night for they have had to adapt to a diet of mainly seaweed which means eating according to the tide times. As a result, they have developed an instinct which enables them to know the state of the tide with their inbuilt alarm system enabling them to rise to their feet just as the tide is about to ebb. In haste, every flock will follow the retreating sea, with each beast competing to munch on the cleanest blades. Some are even willing to swim into the ebbing water to be the first to reach the best pickings. Due to this dietary dependence on seaweed, they are unable to eat too much grass as its copper would poison them. This breed is also uniquely not entirely vegetarian, being able to digest the feet and legs of dead seabirds.

The breed's coat is naturally impregnated with lanolin which repels the weather and so protects the sheep. Shearing by machine would leave their skin too bare to withdraw salt water so this has to be done by hand, the shears leaving just over an inch of wool across the skin. As mentioned at the end of my last article, tradition dictates that shearing is done on the first new moon closest to the end of July or beginning of August.

One other peculiarity to the breed is something that would bring nightmares to modern farmers striving for standardisation. For these sheep will run together on the shore, preventing individual owners from selecting specific rams for breeding with their ewes. This 'breeding-free-for-all' has led to a remarkable range of wool colour, including chocolate brown, steel grey, black, white and cream. It is an individuality in the breed that the crofters take pride in and is something they do not plan to alter. And to be honest, I don't blame them.

Have

a safe and peaceful Christmas.

Steve McCarthy

33

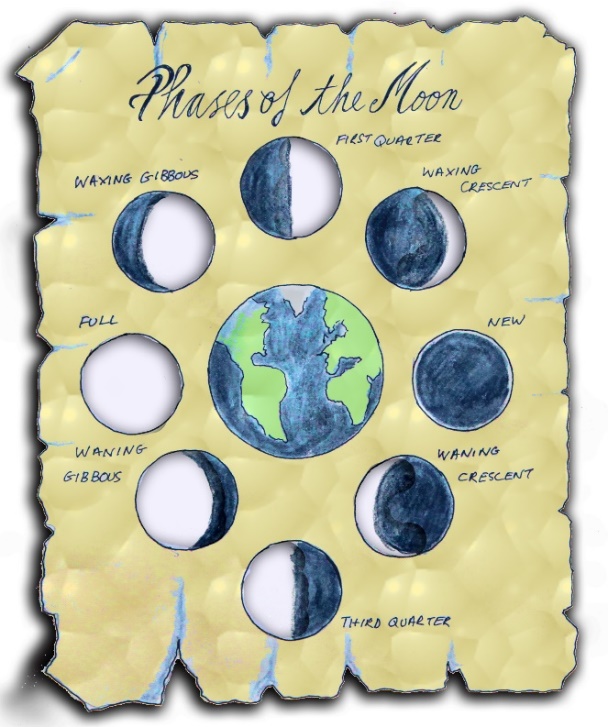

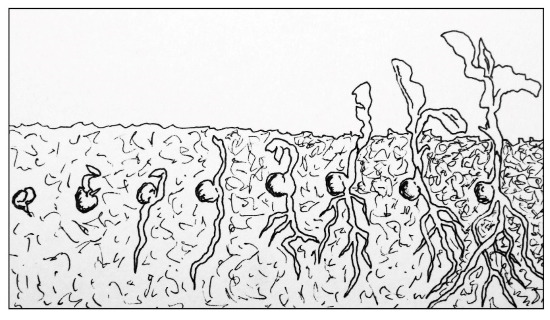

RURAL

REFLECTIONS - 101

The other day I came across a quote

relating to the sun's disappearance beneath the western horizon just after the

moon had risen: "Her hour of rest

is haunted, her heart chilled by the cold face of her dead sister".The concept that the face of our neighbouring

satellite is "dead and cold" is an interesting euphemism which I am

certain would have been utterly discounted by our farming ancestors, for in

their eyes, quite literally, the moon's 28-day cycle was very much alive.Indeed, the four phases of the moon, from New

Moon to Full Moon and then round to the next New Moon, have long been

considered a prominent factor in planting schedules. Furthermore, with evidence

now backed up by modern scientific research, lunar farming is just as relevant

today with many modern-day farmers endorsing the practice by utilising lunar

rhythms as a tool for navigating planting periods and harvest dates.

It is a well-known fact that the moon's

magnetic forces affect the tides of our oceans and lead to a swelling in two

tidal bulges on the opposite sides of the earth. These bulges then cause the side of the earth

closest to the moon to be swelled by gravity while the earth's opposite side is

swelled by inertia.

Put

simply, the moon dictates when the tide comes in and when it goes out.Perhaps less well known is that these same

forces have an effect on ground water tables, with the moon's gravitational

pull generating greater water content in the soil, a process which in turn

enhances seed sprouting and plant growth.

Evidence of such benefits to a

plant's metabolism as a result of the moon has been proven through scientific

research on trees where, during certain phases of the moon's cycle, a tree may

have either a spurt in its initial growth or an increase in its germination

rate. This effect also extends to a

variety of plants such as root growth in sunflowers and beans and the extra

absorption of oxygen in plants such as potatoes, carrots and sunflowers.

To explain in simple terms the four

phases [or quarters] of the moon's cycle, it can be best to describe how much

of the moon [it's 'face'] can be seen in the sky. The first phase is from when the moon rises in

the west so close the sun's rising that the moon cannot be observed with the

naked eye and ends when all of the right-hand side of its face can be seen. During this period the moon exerts a force on

the earth's water opposite to that of the earth's gravity.This is considered to be a time when the

ground is consequently fertile and wet and therefore an opportunity for lunar

farmers to plant above ground and in particular leafy crops.With

each passing day of the lunar month's second quarter, a little more of the

moon's face is revealed

in the sky, with its last day occurring when we see the Full Moon. Over this period the moon will still exert a

pulling force on the earth's gravity, making it an ideal time for planting

plants within enclosed seeds such as beans, tomatoes or peas. These first two

quarters, from New Moon to Full Moon, are known as the moon's waxing phase. Lunar farmers see this period as being

suitable for transplanting and sowing any short-lived plants. It is also believed to be a desirable time

for planting plants with the intention to harvest flowers, leaves, seeds or

fruits.

The moon's waning phase occurs during

its third and fourth quarters, from Full Moon round to the next New Moon. In this period its gravitational pull on the

earth lessens and, as a consequence, tides decrease and the earth's soil

becomes drier. During the third

quarter, a period that begins on the day after the Full Moon and finishes when

we see only the left-hand face of the moon, the earth's gravity becomes focused

on a root-ward direction. Lunar farmers

will therefore use this time to plant longer lived crops such as perennials and

root crops such as potatoes and carrots. Finally, during the last quarter of the

moon's 28-day cycle, its lunar gravity [or 'pull'] is at its weakest. This allows the earth's own gravity to exert

its strongest force, in turn pushing water tables to their lowest depths in the

soil. With the soil drier and therefore

easier to work. lunar farmers regard the moon's last phase as the best time for

harvesting, transplanting and pruning. They

also see it as an ideal time for soil improvement such as soil turning, weeding

and adding compost.

As mentioned earlier, the value of

accounting for lunar cycles in farming practices has been carried over from

traditional wisdom. Moreover, so much did our agricultural ancestors place more

emphasis on the lunar months rather than the solar year, they even christened

each month's Full Moon with a name that had its roots in nature. For example, five months of the year had Full Moons named after

animals. January's was traditionally known as the Wolf Moon, named after the

howling wolves, while March has the Worm Moon because of the earthworms that

come out at the end of winter. The Full

Moon in July is known as the Buck Moon to signify the new antlers that appear

on deer bucks' foreheads around this time and in August we see the Sturgeon

Moon, named after the large number of fish in the lakes where the Algonquin

tribes of East Canada fished. Finally, the

Beaver Moon, which this year will rise on 19th November, is according to

folklore named after beavers who become active while preparing for the coming

winter.

The names of two Full Moons traditionally relate to flowers.April's is known as the Pink Moon from the

pink flowers of phlox that emerge in early spring whilst the Full Moon in May

is simply called the Flower Moon to reflect the abundance of flowers that bloom

during this month. A further two Full Moons have links with the

weather, February's known as the Snow Moon and December's the Cold Moon. Some North American tribes named February's

Full Moon the Hunger Moon due to the scarce food sources during midwinter,

while June's is called the Strawberry Moon to reflect the little red berries

that ripen at this time. On 20th October

this year we will see the rising of the Hunter's Moon, a Full Moon that

represented a traditional time when people in the northern hemisphere spent the

month preparing for the coming winter by hunting, slaughtering and preparing

meats. The Full Moon in July is also

known as the Hay Moon while other names for August's include the Barley Moon

and Grain Moon. Corn, meanwhile, is a feature of three Full Moons. In May we

see the Corn Planting Moon, in August the Green Corn Moon and in September the

Corn Moon. Finally, there is the

Harvest Moon which, as I mentioned in last October's article, is the only Full

Moon that can occur in one of two months, September or October, depending on

which month's Full Moon is closest to the autumnal equinox.For

example, this year's Harvest Moon occurred on 21st September, with the equinox

on the following day, while last year's rose on the 3rd October.

Farming by the lunar calendar, however, both traditionally

and in modern times, is not just limited to crops. On North Ronaldsay, for example, sheep

shearing is always done on the first New Moon closest to the end of July or

beginning of August.It is intriguing that this ancient custom is

carried out on a breed that is one of the few links to the primitive sheep that

first came to our isles. But more of

this next time.

Steve

McCarthy

Illustrated by: Paul Swailes

30

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 100

In April 2000, having spent the previous ten years enjoying

holidays in North Devon, we sold our property in Brighton, gave up our jobs and

moved into our static caravan in Berrynarbor. Out of work and with no idea whether we would

find somewhere to live by the end of the season, I woke up the next morning and

thought, "What have we done?" But sometimes in life you have to trust your

gut instinct; and in our case we were right to trust those impulses. We soon gained employment and, just before

the site closed for the year, we found a bungalow in which to live on the

outskirts of Ilfracombe. There was,

however, one consequence of that initial move to Berrynarbor that I did not

envisage; having popped into the local village shop to purchase some goods, I

also picked up, like I did on all our previous holidays, the latest copy of the

Newsletter. Reading the editorial, I noticed how Judie

never forgot to express her gratitude to the issue's contributors, adding that

she would also appreciate articles from anyone who had not previously written a

piece. Nothing unusual, perhaps, except that on this

occasion, I had an inclination to put pen to paper.

From memory, that first offering was a ditty to do with how

we had come to move to the area. Similar contributions followed, all being

short lyrical odes. But it was in the

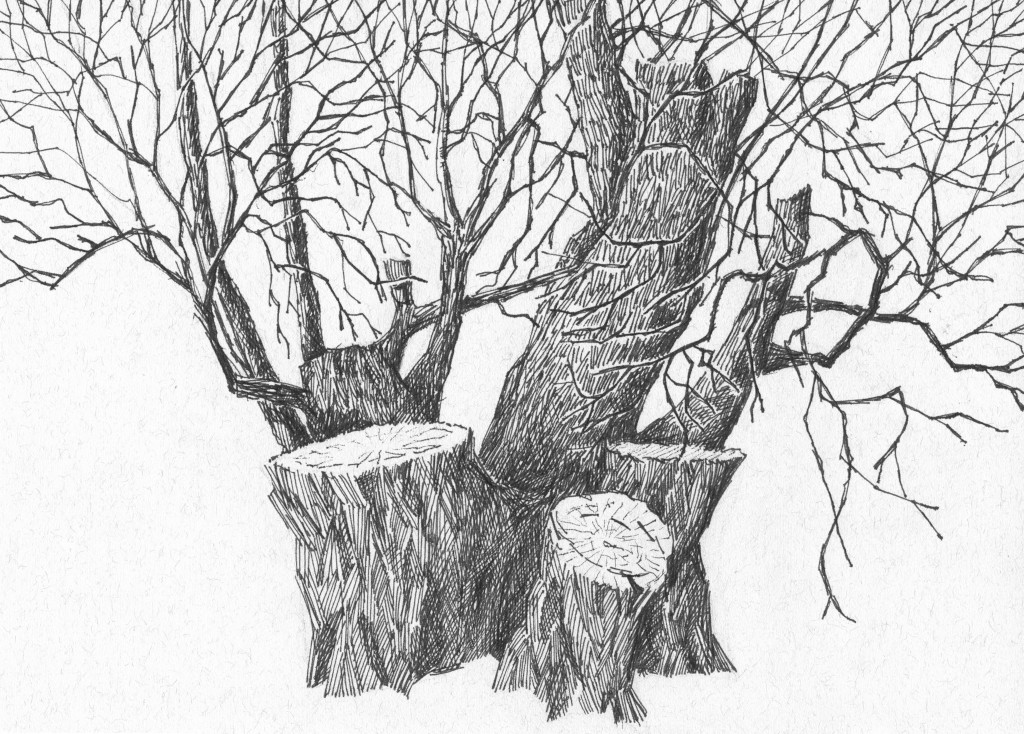

spring of 2001, having witnessed the extensive clearance work in our garden

that encircled our corner bungalow, that I had an urge to put together an

article. The piece made analogies

between our clearance work and the Great Storm of 1987, depicting the latter as

an opportunity for the town in which I lived at the time, Brighton, to have a

re-birth, with mature trees that had stood on guard for centuries being

replaced by fresh, juvenile saplings; and where, in the woods out of town,

grand old trees were allowed a respectable death with their decaying trunks

providing food and shelter for a multitude of creatures. I then

argued that, like the Great Storm, we too had robbed our garden of numerous

trees, not to mention the overwhelming abundance of brambles which had provided

blossom and fruits for wildlife to savour.

But, as with the Great Storm, we

too reaped benefits from our clearance work. Come early spring, a breathtaking carpet of

snowdrops appeared, followed by a mass of miniature narcissi and finally a

dazzling display of tall daffodils which, as I surveyed them swaying in a warm

spring breeze, I likened to the wagging tails of puppy dogs on a parade: all on

show and so much wanting to please us.

Having titled the article "Rural Reflections", I e-mailed

it to Judie and soon received a grateful reply, along with that renowned,

well-intentioned editor's question, "How about another one for the next

issue?" And so here we are, a

further ninety-nine contributions on. Who

would have thought?

Looking back, it's interesting to see how many articles

have, like that first offering, made analogies between mankind and our natural

world [usually concluding that nature is wiser than man] or involving other

reflective debates. For example, there

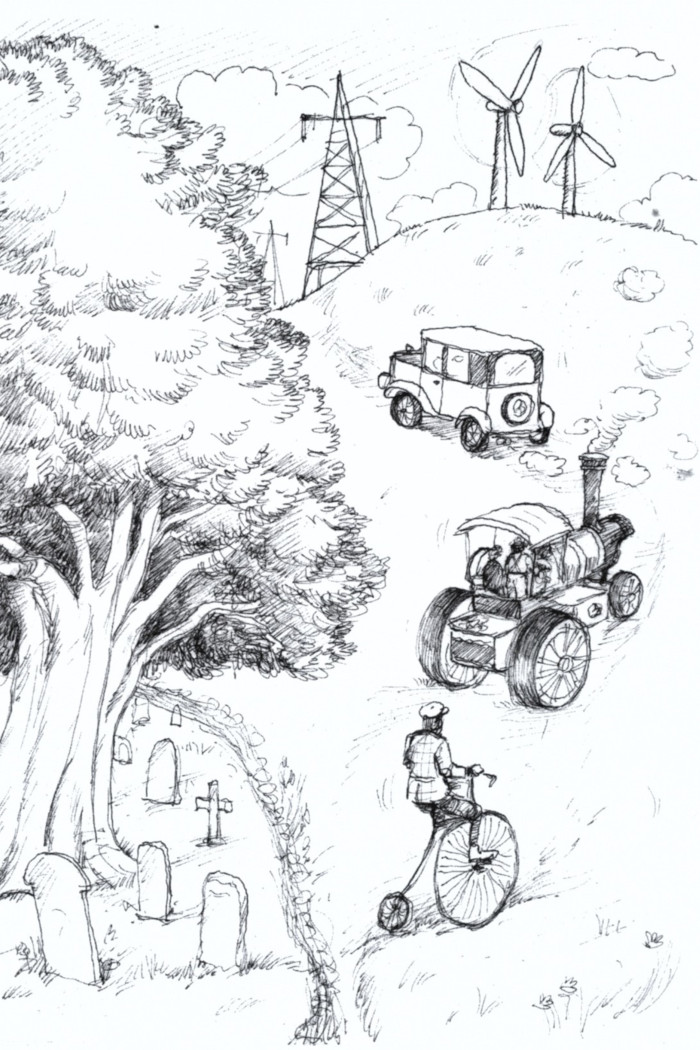

was the piece about the imminent arrival of the wind turbines appearing on the

North Devon landscape; another about local fields being given over to housing

developments and one other debating the dominance of Friesian cattle over

traditional British breeds. In relation to my own doorstep locality, I

also argued whether the felling of trees in my local public woodland for Health

and Safety reasons was, on the other hand, unfairly terminating their natural

life expectancy.

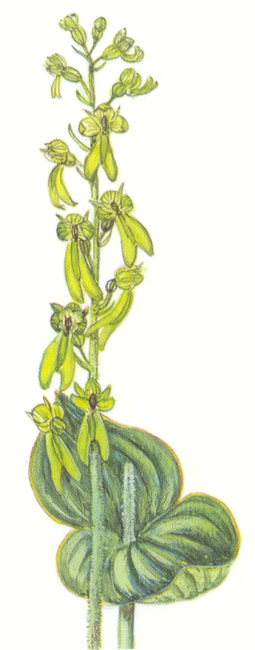

Along with trees, wildflowers have also been the focus of my

attention. For example, a run of articles followed my

observations on the variety of flora observed in the Score Valley from early

spring of one year through to late autumn.

I have also used pieces to

emphasise the benefits to nature that wild flowers can provide in a garden,

finishing one article with the line, "may all your weeds be

wildflowers!" Or as I said in

another piece, it's about regarding those dandelions in a lawn as a blessing to

nature; for whilst they may be spoiling those perfect green lines, they are at

the same time acting as a valuable source of nectar and pollen for our bees,

especially in early spring.

Viewing matters with a positive outlook has also been a

regular feature of my contributions. Without

doubt, becoming a writer for the Newsletter has encouraged me to take the time

to stop, stare and reflect. It also led me to read more books by naturalists,

many of whom I was surprised to discover experienced bouts of depression and

found solace and therapy through walking in the countryside. In my own way I have also written many

articles in the December and February issues in a bid to help readers who

struggle with the winter months. In one

piece I renamed S.A.D. "Spring Approaching Discovery" and in another

concluded that the Newsletter's February issue should be titled the

"Premature Spring" edition. In

others I have made references to how spring's imminent arrival is evident

within weeks of us bidding farewell to the old year and how, even in the depths

of winter, nature is still busy at work despite everything appearing dormant.

All of the seasons and not just winter have been the key

topic in certain articles. One piece again took on that 'glass half-full'

approach, reasoning that whilst the blossom of some trees may be short lived,

their brief displays ensure we appreciate their beauty even more. Another argued the 'for's and against''s' for

each season, but concluded with the question "Who can dislike

spring?" There was a feature on

what colours our countryside provides in autumn beyond the shades of gold,

brown, orange and yellow and one other about how an autumnal walk upon the

Cairn led me to conclude that the season is shifting and now seems later than

when I was a boy.

Other weather conditions have been a

regular topic. A scrutiny of my contributions over the last

20 years reflects how meteorological records have been continually broken, not

to mention the rural impact of unseasonable weather conditions. One article, for example, discussed the

benefits of witnessing the increase in bird species in our villages and towns

as a result of severe inclement weather in the countryside. In

another piece I reflected upon the dominance of one particular bird species in

our own gardens wherever we have lived; but more on our numerous abodes later.

Returning to weather related articles,

there was the item about a visit to friends in South Molton close to Christmas

2004. Whilst we ate and laughed, black

clouds gathered and then vigorously discharged their heavy raindrops,

continuing to do so as I attempted to drive back to Ilfracombe late that night.

Rivers burst their banks and drains

overflowed, causing roads to either disappear beneath deep pools of water or

become extensions of parallel rivers. Eventually,

in the early hours of the following morning, I reached home. Yet within days of the incident, my

experience had paled into insignificance when on Boxing Day an earthquake in

the Indian Ocean caused a tsunami which killed over 200,000 people. Nature at its cruellest.

Other significant incidents have

featured. Soon after I began

contributing articles there was the outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease. More

recently it has been the COVID-19 pandemic.

In their own way, both are

examples of our countryside having a respite from the trampling heels of the

human race. During the first lockdown I

wrote a piece about the enjoyment gained from bringing the countryside to my

doorstep by watching the various birdlife in my own garden. It was something I recently discussed with my

elderly uncle who, living in a park home surrounded by fields and woodland,

used the lockdowns to relax on his veranda and observe his natural

surroundings. He explained with glee how much he had learned

about birdlife by just sitting and watching, not to mention how therapeutic it

had been for him. A lesson for us all.

Illustrated by: Paul Swailes

Giving lessons to youngsters, both

directly and indirectly, have also been articles in their own right. Two come to mind. One centred around some youngsters who were

taking it in turns to forcefully push each into a low-growing

shrub in my local park. On politely

asking them to stop, I had to hide my shock when they genuinely assumed that,

with autumn imminent, the plant would lose its leaves and then die in winter,

allowing the park keeper to plant something else in its place next spring. A brief nature lesson followed. Another article explained how I had enabled a

group of local Girl Guides achieve their Duke of Edinburgh Award by assisting

me collate records of wild flowers upon the Cairn during the course of twelve

months. These records were then passed

onto the Devon Wildlife Trust.

The Cairn has been a regular feature of

my contributions during the ten years I lived in Ilfracombe. Indeed, on reflection I should conclude that

my initial articles ignited a desire to learn more about my rural environment

and in turn led me to write a book about the Cairn. Having that book published had been a life

time's ambition and became the feature of another article.

There have been other instances where I

have used my Rural Reflections space to share personal stories. For example, how the countryside was my

therapy and refuge after the loss of my parents; how it provided comforting

memories of Bourton and Gifford, our two black Labradors who were a regular

feature of my early pieces but who are now happily running through the fields

and woods up above; and how, by observing the way in which the branches of all

the trees in my local woodland were intimately touching, it had reminded me of

a get together I had meticulously arranged for my extended family tree.

My 'RR's' have also followed one other

personal aspect in the life of me and my husband - our numerous moves! As already mentioned, the Cairn and the Score

Valley featured regularly during the ten years we lived in Ilfracombe. On moving to Combe Martin it was another doorstep

discovery, Hams Lane [a recommended walk] that I wrote about and in particular

how I gave names to various key points along the route of the path. Our move to Riddlecombe then reflected upon

how it was the first time we had ever lived in a remote hamlet with no

amenities on hand and with the nearest shop two miles away. Yes, waking up to the sight of cows peering

over our back fence was always a joyful sight; but the extent of the isolation

proved too much. A return to

civilisation through our next move to Yelland was, therefore, a relief; and, in

any case, we still backed onto a horse's field and had farmland surrounding us.

But then I lost my job. "Let's move near the M5 corridor,"

we said. "There'll be better opportunities for work." And so the move to Weston-super-Mare.

"We've still got the countryside

nearby," we said. "And we'll soon adapt back to an urban

setting." Except we didn't - and

to think, I even wrote articles at the time convincing myself that we weren't

missing a rural outlook. But who was I

trying to fool? Oh, how we longed for a

countryside view again. So, six years

later, we moved to Minehead.

Our rural surroundings are very much

like North Devon [minus the turbines], except we're on the other side of the

moor! Better still, it's an area that

is relatively new to us, meaning new rural places on our doorstep to discover -

and, no doubt, accompanying articles to follow!

Steve

McCarthy.

14

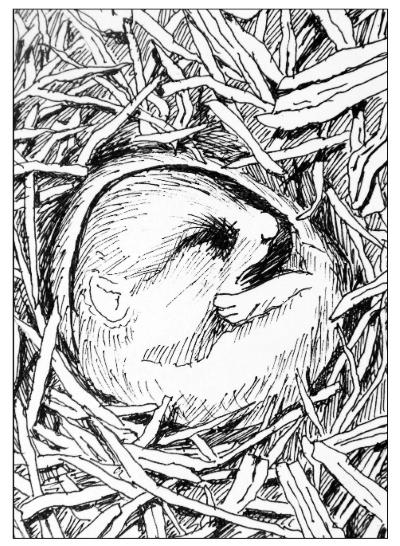

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 99

In the December issue of the Newsletter, I made reference to a violent storm that battered the North Cornwall coast in the mid 1850's. It was a storm that, despite its ferociousness, failed to disturb the slumber of the Reverend Robert Hawker, Vicar of the Parish of Morwenstowe. It was only at daybreak that he was awakened, not by the wind but by the sound of frantic knocking emanating from the front door of his vicarage. On rushing to the door and opening it, Hawker discovered one of his choirboys stood there, his eyes streaming with tears and his hands trembling. Through uncontrollable weeping the boy struggled to describe the dreadful shipwreck that had occurred at nearby Vicarage Rocks. Then, with his hands still violently shaking, the boy raised them up and showed Hawker a creature that he had in his possession and begged the vicar to relieve him of it. It was only later that Hawker discovered why the boy's hands were shaking so. For as he wrote in his diary, "I found out afterwards that the boy had grasped the creature on the beach and brought it in his hands as a strange and marvellous arrival from the waves, but in utter ignorance of what it may be." So what was this nautical arrival that the choirboy had never seen before? A tortoise.

Tommy

As this issue goes to print some garden tortoises will be coming out of hibernation whilst others will still be tucked away enjoying the last few weeks of their winter slumber. Our own garden tortoise, however, was brought out of hibernation at the start of February. Being relatively young, Tommy only needs to hibernate for around three months. This will be extended the older he becomes. Yet some people, so I am led to believe, do not hibernate their garden tortoises at all, whilst a friend of ours is exceedingly pedantic about her tortoises's length of hibernation, tucking them up from Hallowe'en until the 1st of April.

Go on line and you will also find that advice on checking on a pet garden tortoise during its hibernation also varies considerably, from looking in on them weekly to completely leaving them alone. For the record, we do the latter - causing, I will admit, sleepless winter nights of worry; the relief when Tommy's head and legs start poking out of his shell, having been lifted out from his box, is a feeling that only fellow tortoise owners can empathise with! Oh, and in case you're wondering how Tommy keeps warm in those early weeks of post-hibernation, you can be rest assured that he knows to nestle up against the side of our Aga, turning occasionally to ensure both sides of his shell remain at a constant temperature.

Preferences on what owners give their pet tortoises to eat can also differ. When collecting Tommy from his previous owner we were informed [in no uncertain terms] that his favourite food was broccoli; to be cooked until fairly soft and served luke-warm and finely chopped; and she was right. But from the garden, au naturale, there is one wildflower along with its leaves which is also his favourite and from what I understand is adored by all garden tortoises.

The Romans called this wildflower Dens Lionis which translates as Leo Tooth whilst the French name is Dent de Lion, or Lion's Tooth. Both names are based on the jagged appearance of the plant's leaf. We know it, of course, as the dandelion, a flower which is renowned as a weed of garden flower beds and lawns and one that has in recent years spread along road verges on a massive scale being slightly salt resistant. Gardeners seeking the perfect lawn or weed-free flowerbed are also no doubt irritated by the plant's extensive flowering season, beginning as it does in February and lasting through until late summer; the reason, no doubt, why it is the staple ingredient of a garden tortoise's diet. Its early flowering is also a great benefit to our bees, for dandelions are rich in pollen and nectar, the latter something that bees heavily rely upon. It is important to remember that in a bee community only a young mated female will live on to carry hope of a new generation into the new year. Come early spring she knows only too well the need to fill her empty stomach with enough nectar to seek a suitable nest site. Every early dandelion counts. She is also fully aware at the rate at which a field of dandelions will turn to seed. Urgency is therefore paramount.

The dandelion is a very variable plant that botanists divide into hundreds of similar micro species. There are some 150 native species to the British Isles along with a further 100 foreign arrivals that have increased the overall total. Whilst the leaves are rich in vitamins A and C and can be used in salads, the roots can make an agreeable substitute for coffee. It also makes a good homemade wine. A further historical reference to the plant can be found in World War II when dandelion latex provided the Soviet Union with rubber. Gypsies used to call the seed headed dandelion 'Queen's hairy dog flower' whilst other names include seed heads, blow balls, time-tellers and the school boy's clock.

The last name no doubt refers to a school game involving the seed headed flower to tell the time or predict a future event. This would be based upon the number of puffs required to dislodge all the seed heads from one plant. I remember a game at my primary school where the number of puffs determined what age you would live to, how many times you would marry and how many children you would have. But there was one detrimental experience involving these seed heads which is forever lodged in my memory.

Allowed, as we were, to use the adjacent field during our lunch break, a girl in my class began making me daisy chains. Keen to show my appreciation I presented her with a specially chosen bunch of dandelions, hand-picked from the field. Her face was aghast. "You're not my friend anymore and I'm not going to marry you!" she shrieked. "Boys who pick dandelions start wetting beds for the rest of their life." To be truthful, I've never looked at a dandelion in the same way since!

Enjoy the spring.

Illustration by: Paul Swailes

Steve McCarthy

13

RURAL

REFLECTIONS - 98

Whilst living in Brighton in the 1990's,

I attended a creative writing course at a local college. One week our homework was to personalise

something; in other words, to write

about a thing ['it'] as though it were a person ['you']. The tutor told us to think 'outside the box',

emphasising that the 'it' need not be a specific object and added that our work

could be presented in any format;[

composition, prose, poetry or even a letter. From

recall, I wrote a poem about my seizures which, in the opinion of the tutor,

gave a chilling insight into the experience of having one especially when read

in the context of 'you' rather than 'it'.

It was also an unexpected

therapeutic exercise as personalising my seizures enabled me to truly express

how I felt about living with epilepsy at that stage of my life.

So, poised with pen and paper on the

last day of 2020, I decided it was time to once again set myself the challenge.

Firstly, to think outside the box and

try not to consider a specific object. How about personalising the pandemic? Or maybe revisiting my epilepsy? Or perhaps personifying a colour, or a sound

or even the weather? Suddenly, I

chuckled, for as I gazed out of the lounge window, I once again relished the

rural view that I was now looking out upon and compared it to the outlook from

my home twelve months ago, thanks to moving last September from a town which I

decided would be my subject matter. And the format? For some reason I felt compelled to write a

letter.

Dear

Weston super Mare,

It seems like only yesterday when I and

my husband first got to know you. Where did those six years go? Such a pity, don't you think, that our

friendship did not work out? But

please, do not feel guilty, for you are not to blame.

On reflection, it was perhaps our fault

for jumping headfirst into the relationship without first getting to know you. Plus, don't forget, it was us who made the

assumption the relationship would work based on our previous urban friendships

that had been amiable and successful. However, what we had not taken into

consideration was the impact that our fourteen-year fellowship with North Devon

had on us. Put simply, the closeness we

developed with our rural companion meant that any future urban affinity was

doomed from the start. We just failed

to realise it at the time.

As I have mentioned, we did not do our

research. Nor did we consider what we

were sacrificing in my bid to find alternative employment somewhere along the

M5 corridor. We had forgotten how we

always had dog walks literally on our doorstep. Instead we suddenly had to drive everywhere.

Gone, too, were the clean running

streams that our three Labradors adore, replaced as a substitute by the muddy

riverbanks and algae-covered rhynes which edged all of your nearby

fields. Oh, how it was a constant

effort preventing the coats of our Labradors from turning black or

chocolate-brown into shades of green or grey, not to mention adorning them with

that pungent aroma of stagnant water! Yes,

you provided us with local woodland, where, unfortunately, the ground was too

rocky and sharp for the delicate paws of our eldest Labrador.

A pity too, how we found your

surrounding countryside uninspiring; for

we had grown so used to the rolling hills, the steep valleys and the hedge-banks

which our previous companion had aplenty. No doubt many people gain great pleasure from

your Levels, but to be brutally honest, we just don't do flat! And

whilst I cannot deny you provided entertainment and provisions for your

inhabitants, it wasn't for us. Where

were your farm shops, country fairs, village fetes and quaint tea rooms? But, worst of all, we had no outlook and

lived amongst the constant din of traffic. Both peace and rural views were aspects we

had taken for granted whilst being in the company of our old pal. Yes, we thought we would be able to once more

live without them. But we were wrong.

Be pleased for us though, for we have

found a new friend in Minehead. We live

on the outskirts with a rural view across to North Hill and the border of

Exmoor. Needless to say, there are

bountiful supplies of dog walks amongst countryside which looks like a twin of

our old chum, North Devon, and where our Labradors can once again enjoy

fast-flowing streams where they come out the same colour as they went in! We have yet to enjoy the many pastoral

community events on offer but have at least savoured the local amenities

including a farmer's market and farm shop. Oh, how refreshing it is to once more be

within a rural environment! And best of all, serenity surrounds us. No more hustle and bustle.

As I said at the start of this letter,

it was a pity that our relationship did not work out. But let's not be negative. Instead, let us view our six-year friendship

as an experience my husband and I needed to go through in order to realise what

we truly want out of life, and more importantly, to recognise that whilst we

both have urban roots within us, those metropolitan seeds have germinated into

strong rural branches and buds above ground. We are back in the countryside, and we're

here to stay. Best of all, with the

daylight hours increasing and with spring just around the corner, we have so

much to look forward to.

Illustrated by: Paul Swailes

Steve McCarthy

25

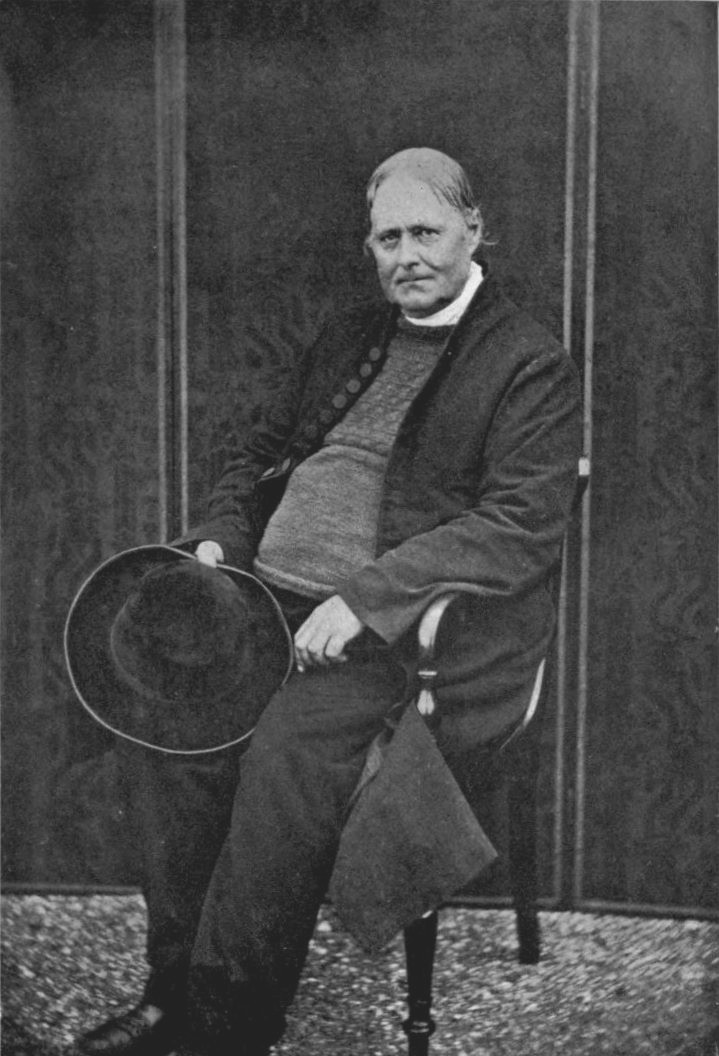

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 97

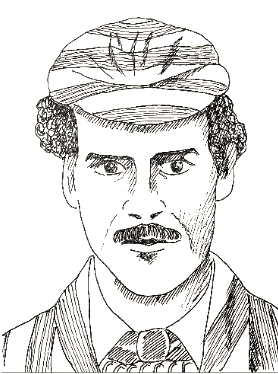

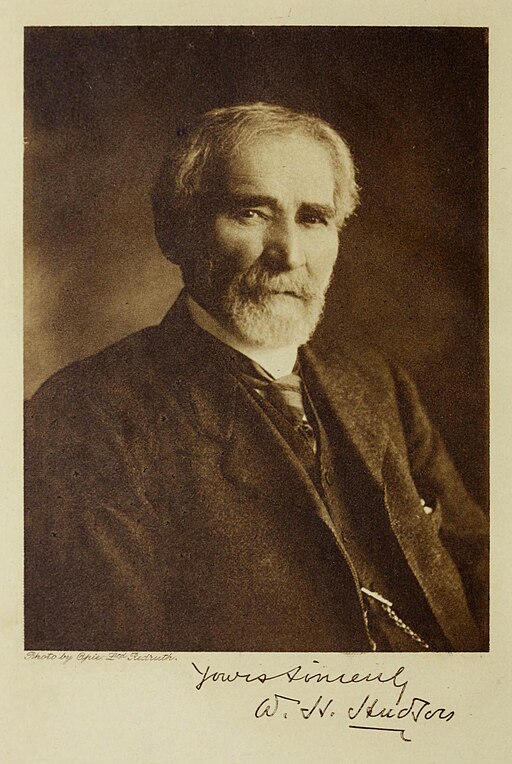

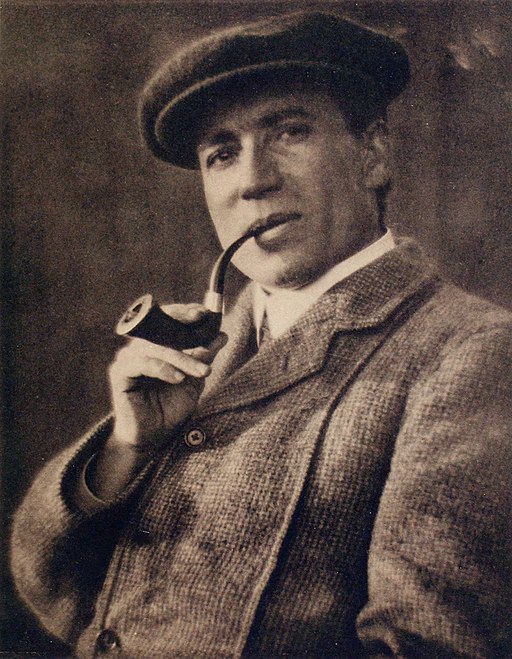

Robert Stephen Hawker : 1864 - Age 61

Richard Budd, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Smuggling from shipwrecks

was once a regular occurrence along the coastlines of North Devon and North

Cornwall. At its worst, the practice

brought out the most calculated and deceitful nature of the coastal villages'

inhabitants. For example, a contemporary

report about the wreckers of Morwenstowe stated that they would "allow a

fainting brother to perish to the sea, without extending a hand of

safety." It was within such an

environment that the Reverend Robert Hawker [b1803], or Parson Hawker as he became

known by locals, chose to carry out his service to God when he became vicar of

the Church of St Morwena and St John the Baptist in the remote rural parish of

Morwenstowe in 1831. Yet by the time of

his death in 1875, this eccentric character, with a strong aversion to black,

was held in such high regard by his parishioners that as a mark of respect at

his funeral they chose to wear purple instead.

In fact, such was his disdain for black, any onlooker was sure to

witness a vibrant choice of dye colouring for his clothing. During church services he donned a yellow

vestment and scarlet gloves; whilst going about the

parish on his beloved mule he would be seen wearing a claret-coloured tailcoat,

a fisherman's jersey with a cross embroidered over his heart and a pink

brimless hat; and if the weather was

inclement he would sport a yellow blanket he had especially sourced in

Bideford, having discovered a hole in its middle which was perfect in circumference

for his head!

But his eccentricity was not just limited to his dress

code. He could also act in ways which

were regarded as somewhat curious. One night, for example, he decided to swim

out to a rock at Bude naked, except for an oilskin wrapped around his legs and

strands of seaweed delicately positioned upon his head to give the impression

of a wig. Once secure and comfortable

upon the rock he began singing in an unearthly voice whilst looking at his

reflection in a glass in order to comb his green slithery hair. The rural natives began to gather on the

shoreline in wonder at their discovery of a real mermaid with hair that

glistened in the moonlight! Relishing

the attention, Hawker repeated the act the following night, noticing on his

arrival that a larger crowd had gathered.

In order not to disappoint his audience, he chose to end his performance

by plunging into the sea and disappearing out of sight. The next evening an even bigger crowd

arrived, the throng now including onlookers from neighbouring villages. This time before submerging into the water he

ended his singing with a vigorous rendition of God Save the King.

Like many eccentrics he was also a loner - perhaps the

reason why he chose such a remote area to ply his trade. However, the best example of his need to be

alone was the hut he erected close to Higher Sharpnose Point, roughly one mile

from Morwenstowe Church. Built out of

driftwood and timber from shipwrecks, Hawker constructed it into the hillside

so he could look out to the Atlantic. This was a place, no doubt, where he

gained inspiration for his sermons and poems.

The original hut has since been replaced by one of mainly timber with a

turf-covered top. Now owned by National

Trust [it is their smallest property], it can be accessed from the South West

Coast Path.

Hawker probably also used his hut to observe the moods of

the weather and sea in order to foresee the likelihood of any shipwrecks; for it was in such a scenario that he carried

out what was arguably his greatest deed.

He had been in the parish around 25 years when on an autumn evening a

violent storm erupted. It rattled the

windows of the old Morwenstowe Church so furiously, Hawker had to shout during

the service so he could be heard above the din. In the churchyard, sycamore branches were

whipped and headstones knocked flat.

The storm raged throughout the night, the doors to his vicarage

clattering and its windows flapping.

Yet Parson Hawker slept through it all.

Only at daybreak did he stir, awoken by one of his choirboys banging on

the front door. "Oh Sir," the

boy cried. "There are dead men on

Vicarage Rocks." The Parson

immediately rushed out in his dressing gown and slippers, ran the quarter of a

mile to the cliffs and descended the 300 feet to the beach. He instantly began bringing to shore

sailors, both dead and alive; and, more

significantly, as locals arrived on the scene and witnessed Hawker's actions,

they instantly did the same. Looting

goods or leaving men to die was not given a second thought, such was the high

esteem in which the parson was held - in an era when, as the saying went, 'save

a stranger from the sea and he'll turn your enemy'. In sheer contrast, however, these locals

respected how Parson Hawker gave every dead sailor a Christian burial and how

he had survivors stay at his vicarage until they were fully recovered.

So what was it about Hawker that led these isolated, rural

and, in some cases, law-breaking locals to change their attitude? Why was this parson held in such high

esteem? To answer these questions, I

believe there are two factors to bring to light. Firstly, he was widely known for his

reckless generosity to the poor of his parish and those who were

shipwrecked. Secondly, people who go

about their lives on an even keel, their temperament always calm and their demeanour

emitting a sense of solidity and security naturally gain respect. Parson Hawker was one such person. For there was an upper stillness in which he

lived. To him the remote, rural village

of Morwenstowe was a truly holy place, his church 'a chancel in the sky'. What's more, it was in that dusty chancel

that he was confident that he could see St Morwena; and whilst nobody knows quite who she was or

precisely what she did to become a saint, Hawker felt he knew her

intimately. But his bond with heavenly

forms extended beyond Morwenwtowe's dedicated parochial saint. In one of his poems he tells of how, whilst

praying in his church, he could hear angelic hymns: 'We see them not - we may not hear; The music of their wing; Yet know we that they sojourn near; The

Angels of the Spring.'

We talk of Christmas as the season of goodwill. However, this year we saw, to quote Reverend

Robert Hawker, the emergence of 'Angels in the Spring' with the onset of

Coronavirus. Tragic though this has been, the outbreak has brought communities

together and led people to go out of their way in order to support vulnerable

neighbours, friends and family during these unprecedented times. Like Parson Hawker, may your acts of

boundless generosity and kindness continue.

Merry Christmas.

Steve

McCarthy

Illustrations: Paul

Swailes

33

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 96

The Harvest Moon is the full moon that appears in the sky closest to the autumnal equinox. It is more frequently seen in September, the equinox occurring on or near to the 23rd and is observed every three years in October. This year it can be witnessed on the 1st October; the same date, by coincidence, that the first Harvest church service took place in 1843, conducted by the Reverend Robert Hawker in his parish church in Morwenstowe. But more of this eccentric character later.

Most people are likely to have heard of the Harvest Moon. Many are also no doubt aware it is the name associated with an autumnal full moon. Perhaps less well known is that every full moon has a name dependent upon the month in which it falls, some years have 13 full moons, the extra being known as a Blue Moon. This October is one such month, the second full moon rising on the 31st. If the Harvest Moon occurs in September then it is also known as the Corn or Barley Moon whilst October's full moon is known as the Hunter's Moon.

Tracking the changing seasons by following the lunar months, rather than the solar year, was common in ancient times and is the reason why full moon names have their roots in nature and their origins in ancient cultures. However, of all these names, it is the origins of the Harvest Moon that is open to debate. Some sources claim it came from Native American month names which, according to the Old Farmer's Almanac, were adopted and incorporated into our modern calendar. European experts, meanwhile, are keen to point out that the Harvest Month is recorded as early as the 700's in both Anglo-Saxon and Old High German languages.

So why is it that the full moon closest to the autumnal equinox is known as the Harvest Moon? After all, the word harvest usually refers to the corn crops reaped from July through to October. One theory connects it to historical records which reveal that its name represented a time when farmers harvested the last of their summer crops in the final evenings of prolonged light before winter came along. In this case, however, the term 'prolonged light' does not relate to the period when the sun is setting and the proceeding dusk. On the contrary, it is referring to the characteristics of the full moon that are unique to this time of year. For the Harvest Moon typically appears bigger, brighter and more colourful than the average full moon.

This is due to two factors. Firstly, its placement in the sky compared to other times of year. Secondly, throughout most of the year the moon rises an average of fifty minutes later each day.

But on several nights before and after the Harvest Full Moon, it may rise as little as 23 minutes later. This allows it to rise soon after sunset for several evenings in a row so that to the naked eye there appears to be a succession of full moons. More significantly, it provides an abundance of bright moonlight early in the evening which is a valuable aid to farmers when harvesting their crops.

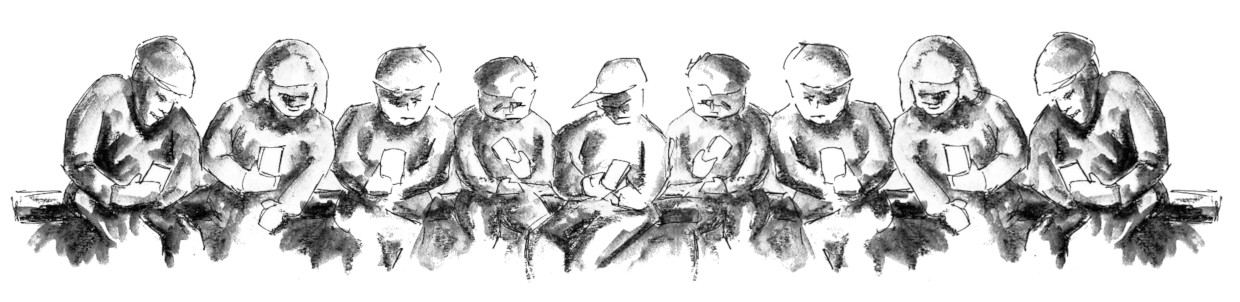

Of course, modern harvesting bears no resemblance to traditional methods. I was reminded of these old-fashioned techniques recently when reading Before The Lake - Memories of Chew Valley, in which the editor, Leslie Ross, has collated recollections of people who lived and farmed in the Somerset valley before it became a lake in 1956. One contributor recalled harvest time and hay making, explaining how men from the local coal pits, working fewer hours in summer time due to the lower demand for coal, would be keen to help out. The contributor describes these men as 'useful, strong, capable and willing', adding that they 'enjoyed the change of working in the open fields'.

Illustrated by: Paul Swailes

Although not paid well, the coal workers were at the same time grateful for the tea, cider and food brought out by the womenfolk, the contributor emphasising how their home-made bread, cheese, pickles and cakes were served with 'secret pride'. She adds that all the local children would also join in at harvest time, recalling how they tussled over who would ride on the horses drawing the wagons laden with the haystacks and who would sit on top of them!

Trevor Robinson is another author who refers to harvest time in his book Working with the Curlew - A Farmhand's Life. Having initially spent his farming life in Yorkshire, he later moved to a farm near Leominster where over time he came to realise how the farming calendar was programmed in such a way as to bring together all the different forms of agriculture to a common meeting point, whether they be stock or arable. Of all these occasions, Robinson is keen to emphasise that the end of harvesting, a time he describes as 'when all the harvest was in under cover', was one 'of great relief, (having a) sense of achievement (as if) the whole year seemed to climax at this point.' He acknowledges, too, how the Harvest Festival, or Harvest Home as some locals called it, had a great meaning for the farming community. What's more, whilst openly admitting his own scepticism of the spiritual realm, he confesses how heart-warming he still found the Church's recognition of this key event in the rural calendar - and is prepared to admit to singing with great gusto, the hymn We Plough the Fields and Scatter.

Harvesting one's crops can perhaps also be used as a metaphor for our own lives, the drawing in of the evenings a period for us to reflect upon what we have worked for over the last six months and to consider what fruits we have reaped from the labours of our efforts. Are there any loose ends that need tying up in order to be ready to set new goals for the months when the hours of darkness outweigh those of daylight?

I can imagine the Reverend Robert Hawker using the concept of harvesting one's crops as a spiritual metaphor for one of his sermons at a Harvest Service. Maybe he used it at that inaugural service is 1843? He conceived the idea of such a service as a means of giving thanks to God for providing such a bountiful crop to his parishioners that year, inviting them to a Harvest Service where the bread used at the Communion was to be made from the first cut of local corn. These services became an annual event and in time led to the introduction of the Harvest Festival that we know today.

When he came to Morewenstowe Vicarage in 1834, Parson Hawker, as he became known, found that the verger had burnt most of the old chancel screen when tidying up the church in preparation for his arrival. Parson Hawker soon set to, rescuing the remains and fixing them up across the chancel arch. In so doing he managed to use the dusty chancel as an area in which to conduct his services, wearing throughout a yellow vestment and scarlet gloves, no doubt startling the church warden when a pair of scarlet hands were thrust through the screen to collect the offertory bags! In the same year of his first Harvest Service, Parson Hawker also introduced the weekly offering in church. Both eccentric and innovative, there was much more to this Reverend who rose to the challenge of plying his trade in this rural, remote parish with a coastline renowned for shipwrecks and the subsequent unchristian practice of smuggling. But more of this next time.

Steven McCarthy

26

RURAL REFLECTIONS - 95

In the June 2019 Newsletter, Jenny Williams compared the day-to-day life of a butterfly to one that is lived solely in the present moment. She then added that this is something that we can all experience with enjoyment and reward during our time on this earthly plane. My last article was testimony to this, the piece featuring the various bird activity I had observed whilst sat in my back garden. By doing so, I had been able to appreciate my natural environment at a time when, due to the COVID19 outbreak, the government had initially put in place strict safety restrictions on our movements;limitations which as a consequence inhibited usual explorations of my rural locale.